Introduction (from Part I)

Temporomandibular Disorders (TMDs) are a category of at least 40 distinct conditions negatively affecting the function of the stomatognathic system.1 Many TMD conditions include internal derangements of the articulating disc within the temporomandibular joint that is often followed by degenerative changes in the joint.2,3 The degenerative progression is most strongly related to disc displacement without reduction.4 Some studies have found that TMDs are likely to result from the partial or complete loss of molar dentition causing mainly muscular symptoms (orofacial pain).5–7 Others have found that occlusal interferences to function can precipitate TMDs,8–11 while divergent studies have been unable to find any etiologic relationship with occlusal variables,12 especially within short-term and pilot studies.13 A separate skeletal structural issue related to the masticatory system is Angle’s occlusal classifications. There is evidence that Class II occlusal arrangements have a greater propensity toward developing substantial TMDs symptoms, but Class II and other skeletal problems can also result from the structural consequence of TMJ damage.14–16

Congenital conditions such a cleft lip and cleft palate have been shown to reduce the quality of life and masticatory function even after treatment.17 Ehlers-Danlos syndrome is another genetic disorder that increases the propensity toward developing TMDs.18 One recent study concluded that single-nucleotide polymorphisms can aid or abet the development of TMDs after orthognathic surgery.19 Abnormal growth and development have also been identified as contributors to TMDs conditions. Bacterial infections have been found to be significantly more prevalent in TMDs patients than in healthy subjects.20–23

Psychoneuroimmunology has theorized that emotional stress can be either an etiologic factor or an exacerbating factor in precipitating or perpetuating TMD and chronic orofacial painful conditions.24–26 Somatization, recently renamed as Somatic Symptom Disorder (SSD), has been proposed as a primary etiology of at least some TMDs and orofacial pains.27 The Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC/TMD),28 in Axis II, has recommended the Beck Depression Inventory-II to measure depression and the subscale of the SCL-90 to evaluate somatization.29 However, it is common knowledge that SSD cannot be distinguished just by symptoms from underlying physical disease because they share the same symptoms. It was stated in the RDC/TMD that the SCL-90 does not measure somatization. In fact, psychiatry understands very well that all possible physical sources of symptomology must be disavowed before testing for SSD is likely to be efficacious.

The Patient Health Questionnaire-15 (PHQ-15), validated by testing a large normal population, is a fifteen-question anamnestic instrument used by many psychiatrists and psychologists to evaluate SSD in the absence of a detectible indication of physical etiologic symptoms.30 See Figure 1.

Each question is supplied with three possible answers; 1) not bothered at all, 2) bothered a little, or 3) bothered a lot (during the past 7 days). The totaled score ranges from 0 to a maximum of 30. Normative scores across the population are generally less than 5 and increase gradually with age. Moderate SSD is indicated by scores from 10 to 14, while a score of 15 indicates a percentile rank between 92.8 and 99.7.30 Higher scores = higher probability. See Figure 2.

With so many factors potentially contributing to TMDs it is not surprising that controversy has been the most common overall result of TMDs research. A previous study utilizing the Beck Depression Inventory-II compared depression scores from TMDs subjects pre to post successful physical treatment. While most of the subjects had exhibited moderate to severe depression pre-treatment, successful physical treatment reduced all of their levels to within normal limits, removing depression by itself as a potential etiologic factor for the group.31

Objectives

The objectives of this report were; 1) To compare the changes in the PHQ-15 scores to the changes in the Joint Vibration Analysis (JVA) recorded data and 2) to compare the progression of pain intensity, frequency of symptoms and functional restriction scores to the concomitant progression of the JVA data. The Null hypothesis = No correlation between the PHQ-15 scores or any of the symptom mean scores relative to the progression of the JVA data records.

Methods

For this study six private practices specializing in the treatment of TMDs patients were recruited from four countries (U.S.A., Mexico, Brazil and India). Two of the practices (PT & BS) focused specifically on treatment of TMDs patients without serious TMJ involvement, which could also be termed Orofacial Pain due to a preponderance of orofacial, painful, muscular symptoms and an absence of TMJ pain (n = 37). Their treatments were limited to adjusting the occlusion using a well-established protocol for the T-Scan (Tekscan, Inc. South Boston, MA USA) commonly referred to as Immediate Complete Anterior Guidance Development (ICAGD) or Disclusion Time Reduction (DTR).32–39

The other four practices were focused on arthrogenous TMD patients, most of whom had some stage of Internal Derangements of the TMJ from relatively acute to end-stage chronic conditions (n = 43). Their treatment methods were varied and included the individualized application of ULF-TENS, orthotic TMD appliances, NSAIDs, exercises and in some cases orthodontic and/or prosthodontic restorative treatments as the final restoration of normal function.40–44 These four private practices were thoroughly dissimilar, geographically separated and not linked in any manner, with separate treatment philosophies and methods. This was intentional to include a variety of treatment methods from a non-uniform group of practitioners.

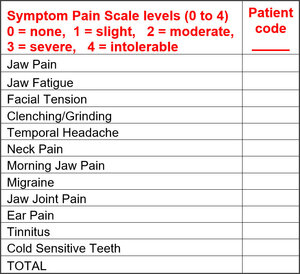

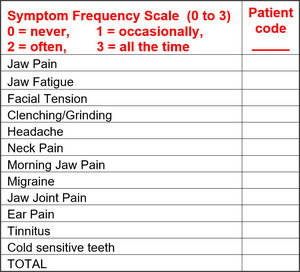

To document the symptom levels prior to treatment each practice agreed to an anamnestic survey of each patient’s Pain Intensity, Symptom Frequency and their Functional Restrictions. See Figures 3 through 5. The questions used were taken from popular symptom surveys (RDC/TMD). After each patient had signed informed consent and agreed to treatment, they were also given the PHQ-15 instrument to respond to. All four of these anamnestic instruments were re-utilized approximately 3 weeks after initiation of treatment and at 3 to 4 months post-treatment at a follow-up appointment.

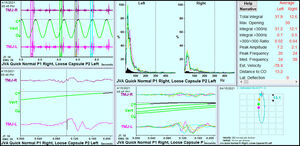

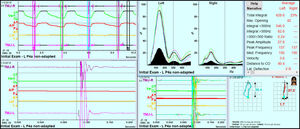

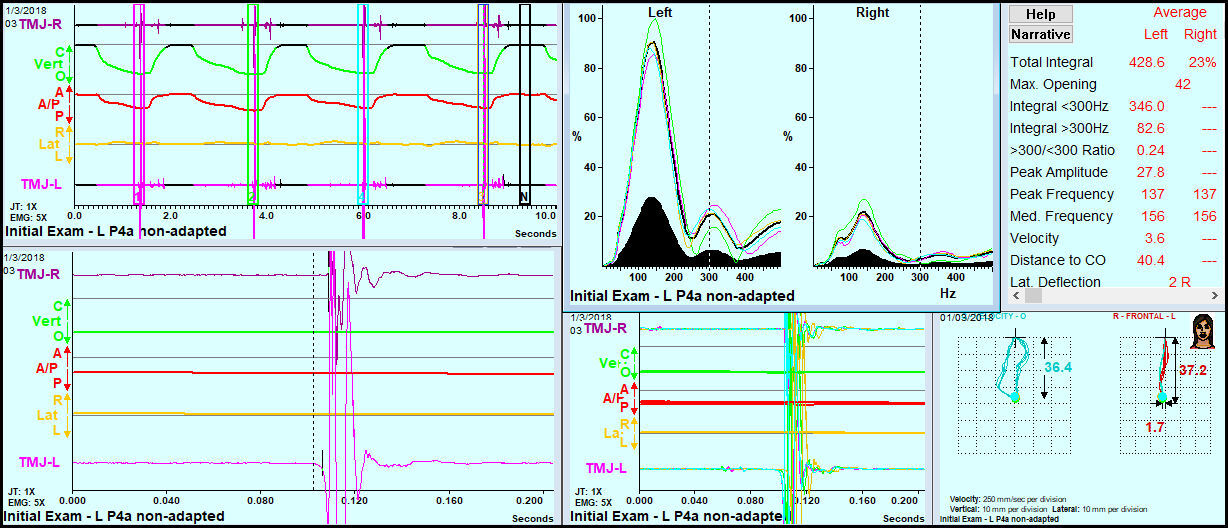

All patients were recorded pre-treatment, post-treatment and at follow-up with Joint Vibration Analysis (JVA) to evaluate TMJ function.45–59 At the same appointments masticatory function was also assessed with combined Electrognathography (EGN) and electromyography (EMG) recordings of gum chewing.60–71 This was done to evaluate; 1) the function of the TMJ and 2) the quality of mastication of a soft bolus using BioPAK software (BioResearch Associates, Inc. Milwaukee, WI USA). The recordings were repeated at each appointment and at the follow-up appointments. The analysis of the mastication data will be reported in the future.

The focus of this second report was on the JVA recordings, which were statistically compared to the symptom levels and to the scores from the PHQ-15. Consequently, the Student’s paired t test was applied to the measured intra-patient data comparisons, making each subject his or her own control. No separate control group was enlisted because the purpose was simply to correlate the JVA measurements with the symptom levels and all subjects’ PHQ-15 scores. Alpha was selected = 0.05.

A total of 80 patients participated, 60 females and 20 males at a ratio of 2.9:1. The mean age was 43.4 (+/- 17.2) years with a range from 14 to 76 years and a median of 42.

While the distribution is not a normal one, it does represent the full range of likely candidates. This is a little older group than many previous TMD studies, which have had their mean ages in the mid to late 30s. Patients were selected sequentially as they agreed to participate. Although not a random process it fairly represents the TMD population both for patients with TMJ involvement (43) and those without TMJ involvement (39). An IRB Exemption for this study # BIRB/100Z/2019 was received.

Results

Significant improvements were observed in all symptom categories. Total pain intensity scores were extracted from the Symptom Pain Scale levels that were reported pre-treatment, 3 weeks post treatment and again at 3 – 4 months post treatment. See Table 1.

In addition to their recording pain scores, each patient was required to record the frequency of their symptoms, which was tracked prior to and throughout treatment. See Table 2.

The group’s Functional Restriction median scores and PHQ-15 Somatization scores were significantly reduced by the treatments. See Tables 3 & 4.

A comparison of the results of treatment between the two groups manifesting either; 1) occluso-muscular or 2) TMJ internal derangement symptoms is shown in Table 5. Those cases that had primary occluso-muscle symptoms and no substantial involvement of the TMJ had their Disclusion Times Reduced (DTR) with (ICAGD) Immediate Complete Anterior Guidance Development. 29–32 The TMD subjects with substantial TMJ involvement (Internal Derangements) were treated with orthotics, TENS, NSAIDs, exercises and other commonly applied methods. Most of these primarily arthogenous patients also had secondary muscular pain complaints that were significantly reduced by treatment as well. It can be seen from this comparison that the orofacial pain patients responded to a greater extent and more quickly within 3 weeks and at the 3 to 4 months timepoint.

JVA Data (see appendix for a description of JVA)

JVA data was recorded bilaterally simultaneously, but analyzed separately. Six parameters from the analysis of the left TMJs were found to be significantly changed towards normal values at 3 to 4 months after the start of treatment. See Table 6.

For the right side TMJs a very similar result was seen. See Table 7.

Correlations were found between the progression of the PHQ-15 scores and the left and right JVA Total Integrals and Peak Amplitudes measured data using Spearman non-parametric correlation methods. See Table 8.

Spearman was also used to compare the progression of Pain Scores to the left and right Total Integrals as well as the Peak Amplitudes. See Table 9.

The progression of the scores for Frequency of Symptoms and Functional Restrictions were also well correlated with the Total Integrals and Peak Amplitudes of the left and right TMJ records from JVA. See Tables 10 & 11.

The Functional Restriction report scores were correlated with the left and right Total Integrals and Peak Amplitudes.

Discussion

Spearman’s Correlation Coefficient is non-parametric and appropriate for survey data because it does not require the assumptions of the Pearson. Its formula is:

\[\rho = 1 - 6\sum_{k = 0}^{n}\frac{d^{2\ }}{{n(n}^{2\ } - 1)}\tag{1}\]

= Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient

= difference between the two ranks of each observation

n = number of observations

Spearman’s Correlation Coefficient was calculated between the three pairs of scores of Pain, Frequency of Symptoms and of the Functional Restrictions vs the left and right JVA Total integrals and left Peak Amplitude. See Figure 6.

rs = 0.93 with (p = 0.00024).

This is a remarkably strong correlation.

The mean and median PHQ-15 scores of the group were reduced significantly as treatment was provided and continued to significantly reduce four months later at the follow-up appointments as did the JVA parameters. From the graph in figure 5 it appears that neither the PHQ-15 scores nor the JVA parameters have reached their absolute minimums at four months after the onset of treatment. It appears that additional time may be needed for some in this group to reach maximum medical improvement.

TMD and orofacial pains that are associated with occluso-muscular TMD symptoms have previously been shown to be significantly reduced up to five years and longer after ICAGD treatment.72,73 These reductions in symptomology do not occur instantaneously, but require some period of time for full recovery. Treatment by appliance also requires six to twelve months to achieve complete recovery.74 This time is required for healing, especially in avascular tissues as in some parts of the TMJ with slow metabolite infusion.75

A period of up to six months or more to successfully reduce painful symptoms in TMJ involved (arthrogenous) cases has been commonly observed. This suggests that attempting to measure SSD in TMD patients prior to the completion of physical treatment and recovery would likely produce a false positive SSD diagnosis. Pain is purely subjective and the etiology can only be determined if the pain can be relieved by some controlled means. Removing the pain pharmacologically does not reveal the etiology, but masks it. Based upon the results of this investigation we reject our null hypothesis of no correlation between the PHQ-15 scores and any of the mean JVA parameters from the data records relative to the progression of treatment.

The Symptom Frequency scores improved significantly after treatment and continued to improve significantly even up to the follow-up appointment three to four months later. This supports the concept that the group responded to all the treatments by reducing the frequency of their symptoms significantly, but symptom reduction is not instantaneous. Three to four months of physical treatments were required before the symptom frequencies subsided, which is a common finding in many TMD treatment studies.76,77

The goal of evaluating functional restrictions is to reveal whether the subject is experiencing difficulty chewing, swallowing, has excessive tooth sensitivity or has been avoiding any tough foods. Although the term functional restriction is often applied just to a limited range of motion, it would be a more appropriate indicator if applied to masticatory capacity. When capacity is only based upon the subjective reporting from the patient, it is a weaker measure than when an objective method is used.78 Masticatory function will be reported on in Part III of this study.

Comparing one obvious difference between the 2 methods of treatment, the ICAGD is focused on the occlusion, specifically occlusal interferences to masticatory function, while the orthotic approach is usually more focused on arthrogenous conditions and the correction of a maxillo-mandibular mal-relationship. The occlusion is more readily corrected by ICAGD when no serious TMJ condition is present, but can sometimes also improve even a patient’s arthrogenous TMD condition enough to reduce symptoms.

Since muscular symptoms can also result from a maxillo-mandibular mal-relationship, splinting can often reduce them as well, especially when the internal derangements are well adapted. However, the success of splinting may need to be maintained with some permanent form of correction (orthodontic or prosthodontic) if a gradual “weaning” of the patient from the appliance does not suffice.

Limitations

While the ICAGD treatments are standardized and have been successfully reported from different practitioners in previous studies,35,37–39 the other four practices providing orthotic-based treatments were quite diverse and the patient populations included TMJ internal derangements that may be more complicated to treat. Since this study focused on treatment outcomes with the subjects only being compared to themselves, no control or placebo group was included. This was also the design because it can be very difficult to maintain an active placebo treatment for several months, especially for TMD subjects.

Conclusions

The PHQ-15 median score of this group of TMD subjects dropped from 10 (medium SSD) pre-treatment to 4 (within normal limits) after physical treatments. Within this group 46 had pre-treatment PHQ-15 scores ≥ 10. A premature attempt to establish a SSD diagnosis using PHQ-15 would have misclassified 58 % of the group as medium level or higher SSD. At the three to four months timepoint 15 % of the group had a PHQ-15 score ≥ 10 (median score 11). The fact that even these resistant cases had significantly reduced their scores from a median of 20 to a median of 11 (p = 0.0116) suggests that they had physical TMD etiologies that responded to their physical treatments. The JVA values decreased in parallel with the changes in symptoms and changes in the PHQ-15 scores with a very high correlation.

While it is plausible that some of the more resistant patients may have some psychosocial aspect to their TMD, more time would be needed to establish that within this group. At 6 months or even at 12 months their scores may also fall to within normal limits.

Clinical Significance

The data in this report supports the theory that the diversity of TMD symptoms can best be explained as predominantly due to physical conditions and only rarely can they be attributed to any psychosocial etiology. Along with reductions in symptomology, this JVA data suggests that physical treatments can also be effective at improving TMJ function, especially in moderately affected cases. Oral diseases and disorders routinely have physical etiologies that need treatment prior to testing for somatization as has been recognized by Psychiatry in Medicine.79

Declaration of conflicts statement

John Radke is the Chairman of the Board of BioResearch Associates, Inc. No other author reported any potential conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

No funding of any kind was received in support of this research activity.