Introduction

Much has been published on Menière’s Disease (MD), which was first identified and characterized by Prosper Menière over 150 years ago.1 Today diagnosing and treating MD among clinicians remains challenging2–7 and as a result MD continues to be a catchall for vertigo of unknown origin. Endolymph Hydrops (EH) remains a histologic finding in most but not all MD cases, while the MD diagnosis remains purely a clinical diagnosis. There is no agreement on the etiology of MD as it relates to endolymphatic hydrops.6,8–12 Current considerations is that EH is a histological sign of the disease rather than a causative etiology.6,9–16 Some research has attempted to induce MD by increasing the endolymph production or limiting its reabsorption through medications. Those models did produce EH but did not produce MD symptoms.17–19 Even if EH does have some influence over vertigo, it does not adequately explain the persistence of tinnitus, ear fullness, or hearing loss progression.

In an attempt to bring clarity to the ENT community a few consensus statements and reviews have been published.6–12 The American Academy of Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery published a clinical practice guideline on MD6 with the stated purpose: “To maximize treatment, it is important to clinically distinguish MD from other independent causes of vertigo that may mimic MD and present with hearing loss, tinnitus and aural fullness.”6 Even though TMD has been known to present with this same presentation of symptoms,20–31 the AAO-HNS fails to make any mention of the similarities in inner ear symptom presentation between TMD and MD anywhere in its 55-page guideline. This is counter intuitive if the aim of their guideline is to distinguish MD from other causes that could mimic MD symptomology.

It is well known that James Costen, an otolaryngologist, read his initial findings of inner ear and sinus symptoms related to disturbed function of the TMJs in 1933 before the Texas Ophthalmological and Otolaryngological Society and was later pubished.32 More recent authors have subsequently labeled his work Costen’s Syndrome, which eventually became known as TMJ Syndrome and currently is labelled as Temporomandibular Disorders (TMD).

In the early 2000’s research spearheaded by Bjorne et al began establishing a link between TMD and MD.22,33–35 Treating TMD patients that were also diagnosed with MD resulted in complete resolution of the MD (and TMD) symptoms or decreased to a level they no longer were life altering for the patient. The symptom resolution was long term as indicated by 3-year and 6-year follow up studies.33,34 Treatments rendered were occlusal adjustments, TMD splint therapy, cervical spine therapy and physical therapy.22,31–35 It is impossible to know if one therapy is responsible for the therapeutic outcome or if it was a result of a synergistic effect of all of the therapies being used in conjunction with each other.

A couple of case studies have shown occlusal adjustments to be highly effective in the treatment of patients that have a diagnosis of Meniere’s Disease.36,37 This study will only use bite revision therapy via DTR in an attempt to bring symptom relief in a cohort of 86 subjects with a diagnosis of MD. DTR has demonstrated effective and long-term symptom resolution in known TMD and Orofacial pain patients.38–47

Objectives

The objective of this cohort study was to perform DTR Therapy on patients with a confirmed diagnosis of MD who presented with long Disclusion Times and/or a bite force imbalance, with high excursive muscle activity levels, all of which could promote MD symptomology. The results of this pilot study will either corroborate or contradict the prior case report’s that observed MD symptom reductions that followed a measured occlusal adjustment therapy.36,37

Methods

Eighty-six patients previously diagnosed by an otolaryngologist (ENT) physician with Meniere’s Disease (MD), were evaluated in two different dental practices that offer specialized Disclusion Time Reduction TMD services. All patients had prior magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which ruled out auditory neuromas. All the patient’s had tried various treatments from dietary restrictions such as avoidance of salt and caffeine to inner ear gentamycin and stem cell injections. None of these treatment options brought about relief for any length of time. While patients were not selected at random, they were random in the sense all were consecutive patients based on their presentation to each of the two dental offices. One general dentistry office located in Eugene, OR where 32 consecutive patients diagnosed with MD were seen successively in the sense whoever walked in and met the inclusion criteria were evaluated and treated. The second dental office is located within the RajaRajeshwari Dental College, Dept of Orofacial Pain under Rajiv Gandhi University of Health Sciences in Bengaluru India. The Dept of Ear Nose and Throat at RajaRajeshwari Medical College was contacted to seek out patients that met the inclusion criteria sent to the second dental office to be evaluated and treated. An IRB approval was requested and obtained for a retrospective cohort study #BIRB/99Z/2022.

The Inclusion criteria were:

-

A MD diagnosis from an otolaryngologist with MRI that definitively ruled out an auditory neuroma

-

The existence of ongoing MD symptomatic episodes

-

28 teeth with symmetrically missing teeth (if one molar was missing on the left side, then one had to be missing on the right side)

-

Near normal occlusal relations with molars and premolars in contact during the right and left excursions

-

Angles Class I and Class III occlusal relations, with guiding anterior teeth that were either in contact, or near to contact

-

Patients that had been previously treated for MD but did not receive symptom resolution

-

Patients 18 years of age or older

The Exclusion criteria were:

-

Severe Class II malocclusions and anterior open bite where anterior guidance contact could not be achieved

-

A previous history of TMJ trauma

-

The presence of unstable Temporomandibular Joint internal derangements verified by CBCT and/or Joint Vibration Analysis (JVA).

-

Patients that had been previously treated with MD therapy that received symptom resolution

-

Patients who had undergone prior TMD therapy, including prior occlusal adjustment treatment.

-

Patients younger than 18 years of age

Informed consent was obtained for each patient undergoing the DTR coronoplasty, and for collecting MD symptom severity, frequency and duration data from questionnaires. Oral health histories were also obtained where the whole participant group reported experiencing MD symptoms. All the group reported fullness in the ear, tinnitus, vertigo (including drop attacks) and hearing loss in at least one ear. Surprisingly the group also reported many TMD symptoms with moderate to severe frequencies and intensities. The TMD symptoms seemed to be randomly distributed and no correlation could be made with any one symptom to the MD symptoms.

Every participant underwent a pre-ICAGD right and left excursive Disclusion Time/muscle hyperactivity evaluation with the synchronized T-Scan 10/BioEMG III technologies (Tekscan Inc., S. Boston, MA USA; Bioresearch Assoc., Inc. Milwaukee, WI, USA). See Figure 1.

Subjects closed firmly into their Maximum Intercuspation Position (MIP) Figure 2, clenched their teeth together for 1-3 seconds, and then completed a single-movement excursion Figure 3 (right or left) until only their anterior teeth were in contact. They repeated the recording so that 2 different recordings were made, one to the right and one to the left. This allowed accurate EMG and disclusion times to be recorded prior to the therapy.

Figure 2 illustrates a closure into the intercuspal position, followed by an attempted left lateral excursion. The patient reported the affected ear was the right one. The right posterior quadrant has the greatest amount of closure force which is 43% of total bite force (black arrows). In general, the EMG recordings for the Temporalis and Masseter should roughly be equal in MIP of healthy subjects. What is observed here is the temporalis muscles are firing 5 times higher in amplitude (blue arrows).

Figure 3 reproduces the same pre therapy scan in Figure 1 but shows the activity early during the left excursive direction and that the patient is locked in on the right side (black arrow) tooth #2. The muscles were hyperactive throughout the scan but peak at 437.9 microvolts during the movement (blue arrow). The pre-op Disclusion time is 0.82 seconds (green arrows). There is no anterior guidance which creates prolonged disclusion over 0.50 seconds and this is time is being reduced with the coronoplasty (green arrows).

Description of the DTR Therapy

The therapy is described elsewhere in detail.38,48 Briefly, teeth were dried on one side of the mouth (top and bottom), then the subjects closed into their Maximum Intercuspal Position (MIP) with 21-micron thick articulating paper (Parkell, Englewood, NY, USA) between the teeth. Then the subject moves into a right excursive all the way out to the tip of the canine, then back into MIP, then this excursive movement is repeated to the left and back into MIP. The pre-treatment recordings then guided the authors to the appropriate areas of occlusal surfaces that necessitate corrective adjustments. The posterior working and non-working lateral interferences are completely removed and centric stop contacts are revised from broad contacts into small pinpoint contacts located on supporting cusps, marginal ridges and central fossae. This is then repeated on the opposite side.

DTR therapy was considered complete when:

-

All lateral posterior excursive interferences are removed

-

Disclusion times had measurably been reduced to < 0.5 seconds in both directions

-

Habitual closure contacts were located solely on cusp tips, fossae and on marginal ridges

-

T-Scan revealed that patient self-closure into MIP achieved bilateral simultaneous force rise

Post therapy recordings were taken in the same fashion as the pre therapy recordings to confirm disclusion times were correct. Patients were seen at day 1, at one month and 3 months to refine the above procedure. This allowed muscles to heal after the occlusal corrections. At each of the 3 visits, subjects filled out new questionnaires regard symptom frequency, duration, and intensity. All subjects’ self-assessment data were subjected to the Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test. Disclusion Time values and EMG levels pre and post therapy were subjected to Student’s paired t-test (Alpha = 0.05). This concluded both the treatment and data collection stages of the study.

Figure 4 is the same patient as in Figure 2 post treatment for comparison following the DTR therapy. The force outlier on tooth #2 was corrected from 19.1% to 9.3% (black arrows). Post therapy the hyperactive muscles have decreased from 366 R /367 L microvolts to 60 R/60 L microvolts (blue arrows). The Disclusion Time was reduced from 0.82 seconds in Figure 2 to 0.29 seconds (green arrows).

Figure 5 is a post operative scan compared to pre-treatment scan in in the same manner as Figure 3 with the cursor moved into the part of the scan that reveals left movement. Canine guidance took over as the teeth came apart and the non-working interference on tooth #2 was also corrected (black arrow). Note that EMG data from Figure 3 was 437.9 microvolts which dropped to 7.9 microvolts post DTR (blue arrow) in Figure 5.

Results

The goal of objectively reducing the subjects’ Disclusion Times was achieved as shown in Table 1. These were statistically significant reductions (p < 0.00001) for every subject in the MD cohort out to six months. There were statistically significant reductions in the group muscle activity level EMG means of all 4 muscles (right and left temporalis anterior & right and left masseter muscles) from pre to post therapy that coincided with shortening the disclusion times. See Table 2.

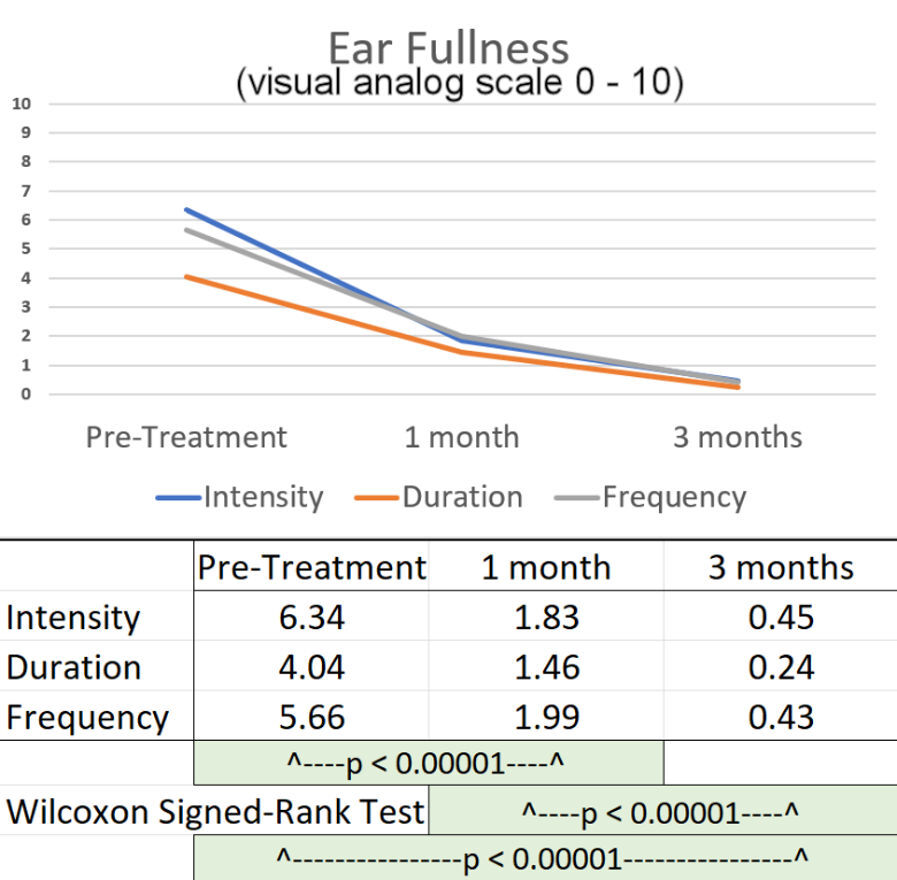

VAS scores were averaged for the 86 subjects for intensity, duration and frequency of vertigo, tinnitus and ear fullness at day 1 pretreatment, at one month and at three months post therapy. See Figures 6 – 8. Hearing loss improvement could not be quantified or tabulated but many subjects stated that their hearing had subjectively improved. Audiometric examination was not consistently accomplished as part of the diagnostic process for most of the subjects and no follow-up test was possible because the “gold standard hearing test” was not readily available for the two dental offices.

Some researchers caution that the diagnosis of MD can be rendered in the absence of all of the symptoms and hearing loss is not needed to render the diagnosis.16 This would create many false positive diagnoses if 25% of the symptoms could be omitted from the clinical assessment for MD.

The 3 clinical symptoms, the only ones that could be subjectively quantified by the patients (VAS), were vertigo, tinnitus and ear fullness. The subjective levels of vertigo were dramatically reduced significantly (p < 0.00001) at one month after DTR treatment and continued to reduce at three months post-DTR (P < 0.00001). See Figure 6.

Equally dramatic significant reductions in Tinnitus were observed at one month post treatment and again at three months post treatment. See Figure 7.

Significant reductions in the subjective sensation of ear fullness were observed at one month post treatment and again at three months post treatment. See Figure 8.

Discussion

The findings of this 86-cohort study corroborated the prior MD clinical reports36,37 in that shortening the Disclusion Time with ICAGD in these 86 subjects, resolved many MD symptoms within a short period of time, that lasted through the 3-months period of observation."

In the previous two DTR/Meniere’s case studies36,37 it was hypothesized that there are only four possible explanations for the observations made in the treatment of MD patients by DTR:

-

MD is a real subset of TMDs.

-

MD was a misdiagnosis, and the patient really suffered from a TMD variant.

-

The patient had two different active disease states occurring concurrently, that resolved simultaneously following DTR therapy.

-

There exists one specific type of MD that involves dental occlusion.

Given the statistical distribution of these results, the simplest explanation is patients suffering from TMD symptoms were erroneously diagnosed with MD. The recognized etiology of MD cannot contain the actual causal factor of this disease process. Otherwise, the authors would have observed a bimodal distribution of subjects where positive outcomes were observed for participants with an underlying TMD diagnosis while a separate peak for subjects that gained no benefit from the treatment for participants with a true MD diagnosis. Even if EH is the cause of vertigo, it does not adequately explain tinnitus, ear fullness and hearing loss. The subjects in this study reported improvements in ear fullness, vertigo, tinnitus, and hearing loss, which are the clinical symptoms used in the diagnosed of MD.

The least responsive subject’s intensity of tinnitus dropped from 10 to 2, the frequency of tinnitus from 2 to 1, but the duration of tinnitus remained at 5, unchanged at 3 months post DTR. However, that subject’s vertigo reduced in intensity from 9 to zero, in duration from 5 to zero and in frequency from 5 to zero. The ear fullness intensity reduced from 7 to zero, the duration from 4 to zero and the frequency from 3 to 1. In total even the least responsive subject received a significant reduction in overall symptoms. It would not be credible to claim that any of these 86 subjects diagnosed with MD did not respond positively to occlusal adjustment via DTR. Unless there is another variant of MD that was somehow not included within this sample of 86 MD patients, it would appear that MD is very responsive to DTR treatment. Perhaps the reason the disease is so enigmatic is because medicine and dentistry have been looking under the wrong stones for answers.

There exists a handful of treatments for MD with inconsistent outcomes most only accomplishing temporary relief.49–54 Current treatment options that are the most efficacious are more invasive and pose a greater risk for hearing loss.55 To be clear, these authors are not advocating just any TMD/TMJ therapy as a first step before inner ear injection or surgeries are attempted. The DTR therapy rendered in this study contains very strict protocols with specific biometric endpoints that have been shown to bring substantial relief to patients diagnosed with MD.

The literature is incorporating more symptoms that are known TMD symptoms into the MD landscape instead of completing a comparison in symptoms between the diagnoses. It must be stated it has already been reported that 90% of MD patients did have neck pain and or headaches. This included tightness in the neck and or asymmetry of the shoulders.56 Postural problems with a component of myofascial problems “are the real culprit which lead to a series of events with end organ affection at inner ear level causing vestibular symptoms.”56 This phenomena has been observed in other parts of the body where one hypercontracted muscle sets off a cascade of other muscles to behave in the same manner making up a chain of tight muscles.57–59 Also some researchers have proposed an association between migraine and MD, where MD patients have migraines 4 time more often than controls.60 Some researchers have reported observing MD in patients as young as 6 years old.3,61–64 “Chronic recurrent headaches occur in approximately 40% of children at age of seven, increasing to 75% by the age of fifteen years.”65 These two disease processes and the age of possible onset is interesting because dentistry observes that the first adult molar erupts around age 6 and the second adult molar around the age of 12. Furthermore, some have found associations involving MD and vestibular migraines,66 both having headaches and migraines. Interestingly, these researchers stated “neither the decision tree analysis nor the logistical regression analysis could reliably discriminate VM from MD.”66 The authors suggested MD and VM may share similar etiology.66

This study supports the concept that rather than being separate entities, MD and malocclusion are one disease process with two different diagnoses depending on which professional confirms the diagnosis: otolaryngologist or dentist. Insight and treatment into the actual etiology of MD can prevent symptom reappearance as well as progression and worsening of the disease process. The authors propose the American Academy of Otolaryngology –Head and Neck Surgery adopt a symptoms screening protocol to include Menière’s Disease within the category of Temporomandibular Disorders (TMD) in the future to avoid needless treatments and wasted resources. In the appendix the authors have included a symptoms sheet that might be a good starting point. The symptoms included here are also known as TMD symptoms.

Limitations

Despite the very small p values suggesting a high statistical significance in the reduction of MD symptoms there were no control subjects. This should be done in the future with some of the subjects randomly assigned to a control group and the remainder assigned to the treatment group. This study attempted to determine a measured effect of DTR occlusal adjustments using the subjects as their own controls. To compensate for this limitation many self-report questionnaires were used to determine the improvements in MD symptoms from pre to post DTR treatment.

Conclusion

Eighty-six subjects with a confirmed diagnosis of Meniere’s Disease experienced reductions in frequency, duration and intensity of their MD symptoms following reductions in Disclusion Time and muscle activity via DTR through computer guided coronoplasty. Although occlusion has been overlooked in most of the medical and dental literature as a possible etiology of MD, the results of this study point to malocclusion, specifically bite force and bite timing, as the etiology for the symptoms in this group of subjects diagnosed with MD.

Note

This data set will be used in four different articles. Part 1 evaluates patients diagnosed with MD and how DTR improves the clinical symptoms that are used in the diagnosis of MD. Part 2 will review EMG and EGN data of Masticatory function. Part 3 will review Joint Vibration Analysis changes and part 4 will address TMD vs MD and Somatic Symptom Disorders from PHQ-15 scores and functional scores, all to shed new light on MD etiology.

Statement of Possible Conflicts

Drs. Ben Sutter, Prafulla Thumati, and Roshan Thumati claim no conflict of interest. John Radke is the Chairman of the Board of BioResearch Associates, Inc. the manufacturer of the BioEMG III. He receives no commission or other monetary incentive from sales of the T-Scan 10 or the BioEMG III.

Statement of Funding

No funding from any source was provided to complete this study.

__but_with_the_cursor_set_in_the_beginning.jpg)

._redu.jpg)

__but_with_the_cursor_set_in_the_beginning.jpg)

._redu.jpg)