INTRODUCTION

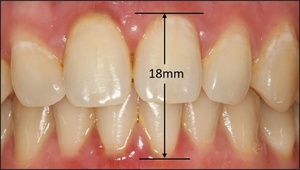

The Shimbashi measurement is the distance from the cementoenamel junction of the upper incisors to the cementoenamel junction of the lower incisors. See Figure 1. For Class I subjects a Shimbashi measurement between 16 to 20 millimeters in centric occlusion has been claimed to be ideal, but without much support. It has been considered as a useful guideline by clinicians since the mid-1980s when evaluating the vertical dimension of prosthodontic and orthodontic patients.1 It has been reported that patients with severely worn dentitions with malocclusions often exhibit a Shimbashi measurement far below 16 mm.2

The Shimbashi measurement evolved during the 1980s from the measurements of Cal Moss, the owner of a dental lab in Waukesha, WI and Dr. Henry “Hank” Shimbashi, a dentist practicing in Drayton Valley, AB Canada. Purely out of curiosity, Mr. Moss started routinely measuring the distance from the cementoenamel junction (CEJ) of a mandibular incisor to the CEJ of the opposing maxillary incisor on the TMD patients’ models sent to his lab.3 For comparison, he also measured many non-TMD cases he received. After hundreds of cases had been measured, he concluded that the distance often appeared to be shortened in many TMD patients. His suspicions were communicated to Dr. Henry Shimbashi in Canada.

While practicing in Drayton Valley Dr. Shimbashi began taking the same measurements on his patients and soon arrived at the same conclusion. In addition to the Shimbashi measurement in occlusion, Dr. Shimbashi also used a K-5 Mandibular Kinesiograph (Myotronics Research Inc., Seattle WA USA) to register the mandible at rest. He found the average distance in occlusion for normal control subjects was about 18 mm as well as for TMD patients with a neuromuscular bite registration in place. The Shimbashi measurement at rest usually added about 1 or 2 mm to the vertical dimension. Using these measurements, he designed an articulator system called the SS19 that revealed the changes in sagittal condylar position when a neuromuscular bite record was mounted. Although never published by Dr Shimbashi, the concept of the “Shimbashi Measurement” was adopted by many dentists from his frequent lectures that he gave in many locations around the U.S. and in Canada.

Dr. Shimbashi understood physiology and realized that biology is variable as well as adaptable. Thus, he knew that average values can be used as a rough guide, but they are never strictly applicable to individual patients. Thus patient “A” might function asymptomatically with a short measurement while patient “B” could exhibit serious symptoms of dysfunction with the same Shimbashi measurement, even when all else appeared to be equal. He theorized that increasing the Shimbashi measurement for the symptomatic subject could improve adaptability and reduce symptoms just as any oral appliance often does. He found that a dysfunctional patient with a short Shimbashi measurement could be relieved by increasing that distance with a very simple mandibular appliance. This could be followed up with a permanent prosthesis if needed or orthodontic correction according to the patient’s desire. It is of note that collapsed posterior occlusions due to missing molars that decreased the Shimbashi measurement were more common in the 1980s among TMD patients than today mainly due to the addition of fluoride to toothpaste and public water systems. Today some question the advisability of the fluoridation of public water systems for overall health, but the subsequent reduction in dental caries is undeniable.4–6

Sierpinska et al tested the “Shimbashi” hypothesis on 50 otherwise asymptomatic subjects (34 males) with advanced tooth wear restoring them to a more normal Class I CEJ-to-CEJ measurement of 17 -18 mm.7 The average increase in the vertical dimension was 4.5 (+/- 1.5) mm. Significant improvements (p < 0.05) in cephalometric radiographs and EMG muscle activity were recorded up to 3 months post treatment. Restoration of anterior facial height was noted post treatment as a reduced SNB angle, a significantly increased ANB angle (p < 0.002), decrease inter-incisal angle (p < 0.002), increase N-Go-Me angle (p < 0.001), an increased Basal angle (p < 0.001), and a decreased Facial Axis angle (p < 0.001) when compared between pre and post treatment cephalometric x-rays. Significant improvements were also recorded in EMG muscle activity (p < 0.05). These authors concluded that several benefits were received by the subjects after vertical restoration of a more normal vertical dimension.

Joy et al recorded the Shimbashi vertical dimension of occlusion of 120 patients distributed equally with 3 grades of increasing severity of temporomandibular disorders, all with less than 18 mm Shimbashi distances.8 A gender balanced 40 subject asymptomatic control group was also measured for Shimbashi. All 3 TMD groups were > 80 % females. Shimbashi measurements were taken with a digital vernier caliper and with lateral cephalometric radiographs of the TMD patients and controls. They found that the control subjects mean Shimbashi measurement (18.43 mm) was significantly greater (p < 0.05) than the mild TMD subjects (15.13 mm), moderate TMD subjects (14.6 mm) and the severe TMD subjects (13.6 mm). Although the radiographic measurements were consistently larger than the caliper measurements between 1 to 2 mm, the same consistent pattern evolved showing more severe TMD cases with shorter mean Shimbashi measurements.

METHODS

One hundred forty-nine sequential patients (72 female) seeking treatment for temporomandibular disorders (TMDs) had their Shimbashi distance measured. After being fully informed and giving their consent, they had their measurements taken during their clinical examination procedures prior to the onset of any treatment. The CEJ-to-CEJ measurements were obtained using a Masel Dental Dial Caliper or comparable device. This group included some cases with malocclusions, altered passive eruptions of anterior teeth, mild gingival hyperplasia, or excessive gingival display, but none included any systemic oral diseases. If the Shimbashi measurement is claimed useful as one indicator of TMDs, these common conditions are likely to be present among some subjects.

A separate asymptomatic control group of 162 youthful subjects (86 female) without malocclusion or periodontal disease consented to have their Shimbashi distance measured for comparison at Rajarajeswari Dental College and Hospital, Bengaluru, India. Analyses of complete group differences as well as gender differences were undertaken using the two-sample Mann-Whitney U test. The control group with a mean age of 21.3 (+/- 1.1) years old was significantly younger than the treatment group (p < 0.05). Alpha was chosen at 0.05.

RESULTS

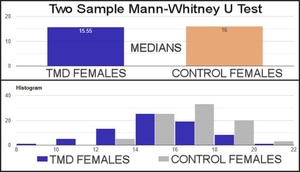

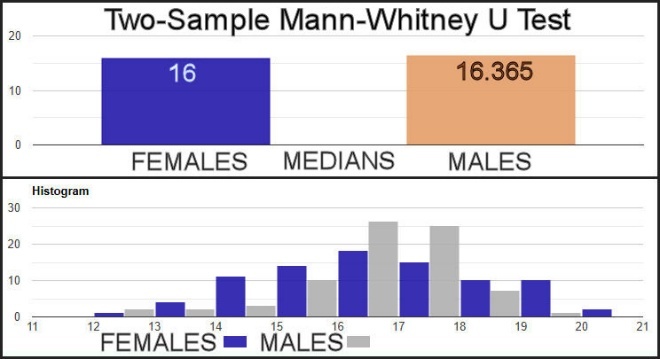

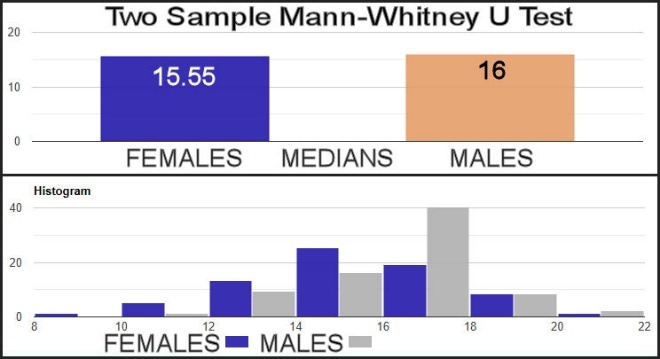

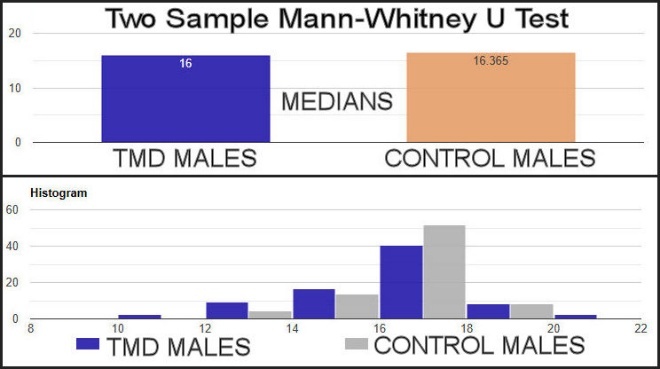

The control group indicated a small non-significant difference in the distributions of Shimbashi measurements between genders as indicated by their mean values, only a 0.01 mm difference in their means and no difference in their medians (p > 0.0869, with the standard effect size very small at 0.13). See Figure 2 and Table 1. However, the TMD subject group showed significantly different distributions between genders (p < 0.0279), but with only a small effect size (0.15). See Figure 3 and Table 1. The Shimbashi measurement of the TMD females was significantly smaller than the Shimbashi measurement of the females of the control group (p > 0.0072), but also with a relatively small, standardized effect size (0.19). See Figure 4 and Table 1. The comparison of the Shimbashi measurement of the TMD males to the control group males was also significant (p < 0.0172), but with a small, standardized effect size (0.17). See Figure 5 and Table 1. A significant difference was also found between the whole TMD group and Control group (p < 0.0011), but also with a small, standardized effect size (0.19).

DISCUSSION

The remarkably similar distributions of both genders within the Control Group supports a contention that the Shimbashi measurement is not different between genders within asymptomatic subjects. See Figure 2 and Table 1. Therefore, the results of this study support essentially the same normal range of the Shimbashi measurement for both genders. Note that the control group was recorded from youthful subjects in India, which may be somewhat different in their absolute values than other ethnic groups, making their 16.3 mm mean value a guide (e.g., a rule of thumb) rather than a universal target as an exact millimeter value.8 The wide range of values (12 mm to 21 mm) within the asymptomatic control group also highlights the fact that a single value or even a narrow range of values cannot be accepted as representative of a “normal” Shimbashi measurement. However, since two standard deviations include 95% of the complete distribution, an expected preferred normal range of 14.7 mm to 19.6 mm seems plausible. This range is for direct caliper measurement and may be 1 or 2 mm less than values taken from CBCT x-rays.8

A significant difference was found between the females and the males within the TMDs group (p < 0.0279) even though the effect size was very small (0.15). Figure 3 and Table 1. Perhaps that could be due to females being more susceptible to various TMDs and therefore being more likely to have a disorder.9–13 The female anatomy has generally more flexible joints, but less durable ones than the male anatomy.14 Or, different hormonal factors could be at play,15–17 but the difference in just their symptomatic Shimbashi measurements is not likely to be sufficient to explain much of the greater frequency that females do seek treatment for TMDs. It has also been common experience that women are more likely to seek treatment for TMDs than men are, but it is uncertain if they are more needful or just more alert to the need of treatment.18

Despite the wide range of recorded normal values and the less than one millimeter difference in their means, the TMD females’ mean Shimbashi measurement was significantly smaller than the control females (p < 0.0072). Figure 4 and Table 1. For the male TMD subjects that difference although even smaller was still significant (p < 0.0172). Figure 5 and Table 1. Although both the median and mean differences were all less than one millimeter between the groups, the consistency of the differences can likely be credited with them being statistically different (p < 0.0011). Table 1.

The critically missing element within any study of vertical dimension is any measure of adaptability. While some youthful subjects may successfully adapt to a Shimbashi of 11 or 12 mm, an older less adaptive subject may not. Joy et al found a correlation between age and a smaller Shimbashi measurement.8 They also found that the Shimbashi decreased with the severity of TMD symptoms, which suggests that a smaller Shimbashi measurement is less adaptable. Sierpinska et al raised the vertical dimension of prosthodontic subjects with severe occlusal wear successfully an average of 4.5 mm while targeting a Shimbashi measurement of 17 to 18 mm.7 The fact that the asymptomatic subjects’ mean Shimbashi measurement range is rather large could explain why occlusal appliances have historically been one of the most efficacious treatments for TMDs. Thus, the increase in the vertical dimension required by an oral appliance can usually be easily accommodated by most patients.

LIMITATIONS

Since all Shimbashi measurements were direct caliper measurements rather than from any X-rays, the exact Shimbashi distance may have been underestimated by 1 or 2 millimeters.8 The relationships between tooth size, Class of Occlusion, age and the Shimbashi measurement were not measured. Those measurements might have added additional elements to the significance of the Shimbashi measurement. The Shimbashi measurement of the control group could only provide a suggestive normative range implying that values outside of it may be problematic. The mean age difference between the older TMDs group and the youthful control group was significant and may have contributed to the smaller mean values of the TMD group.12 However, the benefit of a youthful group was a reduced chance of successful adaptation to occlusal wear and dysfunction that can reduce symptomology and hide any dysfunction that could be present. Thus, they represented a more ideal control group.

CONCLUSIONS

The direct Shimbashi measurement can be a rough guide (e.g., rule of thumb) to a normal range of the vertical dimension, but not a definitive indication of how much or whether to open or close the bite. Although TMDs subjects did have a slightly lower mean value, the difference did not appear large enough to contribute much to the etiologies of their disorders. Only for those few with measurements that fell below the control range (< 12 mm) is it likely that the Shimbashi measurement potentially contributed much to their conditions. However, the current evidence suggests that opening the bite to a Shimbashi measurement something less than 20 mm for prosthetic reasons may be a useful guide to improve the adaptability of TMDs patients. It must be remembered that each TMD patient is a unique individual and that no “one-size-fits-all” treatment has ever been realized. A future comparison of the Shimbashi measurement with the Class of Occlusion, tooth size, and age should be undertaken.

Funding Statement

No funding or in-kind contribution was received for any part of this study.

Disclosures

Ben A. Sutter, DMD - Private practice - Eugene, OR USA, Adjunct Professor UNLV School of Dental Medicine Department of Clinical Sciences and VIVOS Faculty

Prafulla Thumati, MDS, PhD - Professor of Prosthodontics, Rajarajeswari Dental College and Hospital, Bengaluru, India

John Radke, BM, MBA - Chairman of the Board of Directors, BioResearch Associates, Inc., Milwaukee WI USA