INTRODUCTION

Meniere’s Disease (MD) is an idiopathic inner-ear disorder characterized by recurrent vertigo, fluctuating hearing loss, tinnitus, and aural pressure. While endolymphatic hydrops is classically implicated, recent research has made claims of neurogenic and psychosomatic influences in the pathogenesis of MD.1–3 Dysregulation within the autonomic nervous system, chronic stress, and somatic hypervigilance are currently accepted as contributors to symptom variability. Assar Bjorne initiated research linking TMD and MD in earlier studies treating subjects with craniosacral therapy, occlusal appliances, and occlusal adjustments. While Bjorne had remarkable results it remains unclear if any one therapy had a greater impact on symptom resolution or if the results were due to a synergistic effect of all three treatment modalities.4–8

The trigeminal system exerts extensive influence on vestibular and autonomic nuclei. Trigeminal afferents converge with vestibular neurons in the brainstem and upper cervical cord, providing a plausible mechanism by which occlusal imbalance and masticatory muscle hyperactivity can affect postural equilibrium and spatial orientation.9 Excessive trigeminal input may perpetuate sympathetic dominance, muscular tension, and increased perception of disequilibrium.

Disclusion Time Reduction (DTR) therapy, introduced by Kerstein, is a computer-guided occlusal adjustment method that employs T-Scan digital occlusal analysis and EMG monitoring to identify and eliminate prolonged posterior contacts during mandibular excursions.10,11 By reducing disclusion time to below 0.5 seconds, DTR restores balanced masticatory coordination and decreases parafunctional muscle activity, which in turn may reduce trigeminal over-stimulation.12

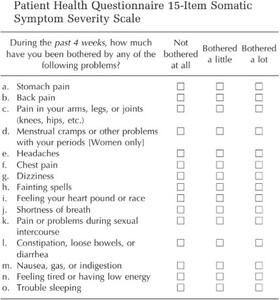

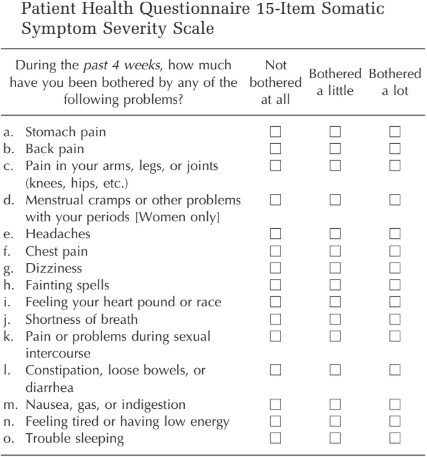

Given that MD symptoms often coexist with apparent somatic complaints such as fatigue, neck tightness, and head pressure, evaluating psychosomatic response is essential.6,13 The PHQ-15 is a validated psychiatric screening tool for estimating somatic symptom burden across medical and dental populations (Kroenke et al. & Häuser et al).14–16 However, neither PHQ-15 nor its subset PHQ-9 are capable of distinguishing somatic symptoms from those with physical etiologies. Therefore, to obtain a reliable SSD assessment using PHQ-15 or PHQ-9, it is critical to establish the absence of any physical etiologies prior to applying PHQ-15 to avoid generating false positive results.17 Combining objective occlusal parameters with the PHQ15 questionnaire offers a unique framework to quantify DTR’s multidimensional impact.

This investigation aimed to assess changes in PHQ-15 scores following DTR in patients with MD and to explore the potential neuromechanical and previously claimed psychosomatic links between occlusal harmony and vestibular stability. Note: DTR significantly reduced to normal the elevated emotional levels suggested by the pre-treatment PHQ-15 scores. This result has again confirmed the unreliability of recording elevated pre-treatment PHQ-15 scores without eliminating physical etiologies and then claiming the symptoms are somatic.

MATERIAL & METHODS

This clinical evaluation enrolled 86 consecutive patients (47 males, 39 females; mean age 50.8 ± 18.1 years) who presented to two specialized centers offering Disclusion Time Reduction (DTR) services and had a prior otolaryngologist’s diagnosis of Meniere’s Disease (MD) confirmed by clinical criteria and MRI rule-out of retrocochlear pathology. The two clinical sites were (1) a private general dentistry practice in Eugene, Oregon and (2) the Department of Orofacial Pain, RajaRajeshwari Dental College, Bengaluru, India. Institutional review board approval or exemption was obtained (IRB/exemption #BIRB/99Z/2022) and all participants provided written informed consent. The study followed the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki.

The cohort size (n = 86) was determined by consecutive case accrual over the study period rather than a priori power calculation. For planning future randomized studies, post-hoc effect sizes observed here (see Results) may be used to estimate the sample size required to detect clinically meaningful changes in PHQ-15 with 80–90% power at α = 0.05. All power/sample-size calculations reported or used in future work should explicitly report the assumed mean differences, standard deviations, and two-tailed test parameters.

Inclusion criteria

-

Age ≥ 18 and ≤ 65 years.

-

Clinical otolaryngologist’s diagnosis of definite or probable Meniere’s Disease, with an MRI excluding retrocochlear lesions.

-

Clinical or T-Scan evidence of occlusal disharmony or prolonged disclusion time on either side (pre-treatment DT > 0.5 seconds typical).

-

Willingness to undergo DTR and attend follow-up visits.

Exclusion criteria

-

Prior otological surgical interventions for MD that produced symptom resolution (e.g., labyrinthectomy, or vestibular neurectomy).

-

Active psychiatric disorders that would confound PHQ-15 interpretation (e.g., severe major depressive disorder, psychosis) unless stable and under care.

-

Severe malocclusion requiring orthodontic or prosthetic reconstruction beyond selective enameloplasty.

-

Prior TMD therapies including occlusal adjustment, stabilization splints, or TMJ surgical interventions.

-

Pregnancy or other medical conditions that contraindicate elective dental procedures.

Baseline clinical assessment and instruments

-

Otologic and vestibular assessment: standardized ENT history and physical exam documenting vertigo frequency/intensity, tinnitus, aural fullness, and hearing status (pure tone audiometry if available).

-

Somatic symptom assessment: PHQ-15 administered in validated local language versions where appropriate; scoring categories used (0–4 minimal; 5–9 low; 10–14 moderate; 15–30 high, 31 + extreme) and instructions given to patients were standardized.

-

Occlusal analysis: Digital occlusal recordings were made using the T-Scan 10 system (Tekscan, Inc., Norwood, MA, USA) synchronized to the BioEMG III electromyograph (BioResearch Associates, Inc., Milwaukee, WI, USA) that recorded bilateral anterior temporalis and masseter activity

-

Joint and masticatory functions were performed. JT-3D electrognathography and joint vibration analysis with BioJVA (BioResearch Associates, Inc., Milwaukee, WI, USA) were performed according to the center’s protocol; parameters and device settings documented.

-

DTR was performed by calibrated clinicians trained in immediate complete anterior guidance development (ICAGD) coronoplasty. To enhance reproducibility, the procedural steps were precisely followed and recorded.

Outcome measures and data handling

-

Primary measure: PHQ-15 total score change (baseline → 1 month and 3 months).

-

Secondary measures: DT (left & right), EMG mean and peak amplitudes, subjective VAS ratings for vertigo/tinnitus/ear fullness (0–10), JVA parameters.

Statistical analysis

-

Descriptive statistics were done by calculating the means and standard deviations, medians (IQR) for skewed variables, and counts/percentages for categorical variables.

-

Primary analysis comparing baseline to 1 month and 3 months PHQ-15 score totals were summed.

-

Correlation and regression analysis were done to estimate independent association of DT change with PHQ-15 change.

-

Software and reproducibility: Analyses performed using SPSS v26 and validated with R scripts

RESULTS

The quantitative impact of Disclusion Time Reduction (DTR) therapy on symptom burden was illustrated by the distribution of individual treatment outcomes across the study cohort. At one-month post-treatment, 85.7% (n=60) of patients exhibited statistically significant reductions in total symptom scores when compared to baseline (p < 0.0000). This percentage increased slightly at three months, with 88.6% (n=62) maintaining or experiencing further symptom relief. Additionally, 5.7% (n=4) at one month and 7.1% (n=5) at three months demonstrated symptom reduction trends (p < 0.10), though not reaching statistical significance. Only a small minority of 8.6% (n=6) at one month and 4.3% (n=3) at three months exhibited non-significant reductions in their symptom scores. All without significant reductions scored 9 or less on the PHQ-15 at the 3-month timepoint. See Table 1.

The group mean PHQ-15 score declined from 8.71 at baseline to 2.06 at one month and further to 1.24 at three months, representing a marked reduction in self-reported somatic symptom burden. See Figure 1. This shift was not only clinically relevant but also statistically compelling, with paired t-tests for both time points yielding p-values < 0.00000, indicating near-zero probability that the observed changes were due to chance. The total group summed score fell from 619 pre-treatment to 146 after one month and 88.2 after three months—an 85.8% cumulative reduction in symptom severity across the group. A subgroup comparison revealed a notable disparity in baseline PHQ-15 scores between the two sites: Oregon patients presented with a mean score of 13.95, while Bengaluru patients averaged 6.76. This difference was statistically significant (Mann-Whitney U (p < 0.0000), with a large effect size (0.73).

DISCUSSION

At one-month post-DTR, 85.7% of patients demonstrated statistically significant reductions in total symptom burden, increasing to 88.6% after three months. These improvements were not only statistically robust (p < 0.0000007 at three months) but also clinically meaningful, reflecting durable relief beyond the short term. The group’s mean PHQ-15 score fell from 8.71 pre-treatment to 2.06 at one month and 1.24 at three months—clear evidence of perceived reductions in somatic distress after occlusal corrections. See Figure 1. 100% of these patients diagnosed with MD in this study exhibited prolonged disclusion times prior to treatment, strongly implicating occlusal dysfunction as a contributor to their symptoms. Long disclusion times and bite force imbalance have been implicated in other medical diagnoses such as Phantom Bite Syndrome (Occlusal Dysesthesia), Trigeminal Neuralgia, Cervical Dystonia, Cluster Headaches and Meniere’s Disease.18–24

This clinical investigation into the application of Disclusion Time Reduction (DTR) therapy in patients diagnosed with Meniere’s Disease (MD) presents a compelling argument for the inclusion of occlusal factors in the broader etiological landscape of MD.13,18,19,25 The findings of sustained symptom reduction across multiple domains—including vertigo, tinnitus, and ear fullness—underscore the potential relevance of occlusal disharmony and masticatory muscle hyperfunction in the perpetuation of MD symptoms.

Chronic pain and functional complaints in MD patients are frequently classified as manifestations of somatoform disorders due to the complete lack of physical ear pathology. However, our findings challenge this assumption. Mechanical factors, such as prolonged disclusion time, likely underlie these symptoms, and their resolution with DTR suggests that not all symptomology labeled as psychosomatic have psychiatric/somatic etiologies. This view aligns with Dworkin’s assertion that misattributing somatic symptoms to psychiatric causes risks overlooking treatable biomechanical dysfunctions, such as in cases of temporomandibular disorders (TMD).26 Although PHQ-15 scores declined significantly post-DTR, it is important to contextualize this tool’s limitations. The PHQ-15 is a subjective, self-assessment instrument, with modest sensitivity (61.9%) and specificity (56.5%).14 It cannot discriminate between symptoms arising from psychological distress and those due to physiological dysfunction. These findings agree with another study where pre-treatment PHQ-15 scores contained high false positive results.27 Therefore, PHQ-15 outcomes should be interpreted alongside objective clinical measures, including EMG, Disclusion Time (DT), and Joint Vibration Analysis (JVA), as well as patient-reported improvements in function.

The subgroup comparison may reflect; 1) regional variations in diagnostic stringency, 2) psychosocial stressors, 3) healthcare-seeking behavior, 4) cultural interpretations of somatic symptoms or 5) just the inclusion of less severe cases in one cohort. However, importantly, both cohorts showed substantial improvement following DTR, reinforcing the treatment’s applicability across diverse populations, even among patients with higher baseline somatic distress.

Moreover, objective metrics supported the subjective improvements. Reductions in disclusion time and EMG activity mirrored symptom resolution. For example, pre-treatment DT values were consistently above the 0.5-second threshold, implicating occlusion. Post-treatment reductions in DT and EMG amplitudes were statistically significant (p < 0.0001), confirming improved neuromuscular coordination.

These findings confirm that the improvements following DTR were not isolated or anecdotal, but rather consistent, reproducible, and sustained across a diverse patient population. The magnitude of change, both at the individual and group levels, supports the hypothesis that biomechanical factors, specifically prolonged disclusion time, can reveal a substantial portion of symptoms traditionally attributed to Meniere’s Disease or other apparent somatoform disorders.28

These results underscore the importance of thoroughly evaluating MD patients for TMDs before confirming a diagnosis of MD. The symptoms overlap - aural fullness, vertigo, tinnitus can lead to false SSD diagnosis, especially in the absence of occlusal or masticatory assessment. 100 % of patients in this study exhibited prolonged disclusion times prior to treatment, strongly implicating occlusal dysfunction as a contributor to their symptoms.Given that DTR therapy is minimally invasive and guided by digital precision tools, its use in MD-like presentations appears justified, especially when conventional otologic interventions offer limited relief or carry significant risks.26,28 DTR, when performed by trained clinicians using calibrated protocols, can serve as a conservative therapeutic step before considering invasive otologic procedures.

Finally, this study prompts a broader reevaluation of how somatic symptoms are interpreted in medical and dental contexts. Rather than defaulting to a psychosomatic model, clinicians should consider mechanical contributors, particularly in patients with symptoms that do not conform neatly to psychiatric or vestibular paradigms. Future research should aim to delineate the mechanistic pathways by which occlusal disturbances contribute to vestibular and autonomic dysfunction, incorporating imaging, longer follow-up periods, and multidimensional outcome metrics.

Clinical Significance

A person’s somatic response can create a “vicious cycle” that worsens the symptoms and course of Meniere’s disease. While stress does not cause the condition, psychological reactions like anxiety and depression can trigger and intensify attacks, which increases psychological distress. Labeling a patient’s MD as a somatic symptom disorder is not helpful when treating Meniere’s disease.

As demonstrated by this study, DTR has been shown to reduce the PHQ-15 scores, indicating an improvement in emotional distress. Hence, for clinicians encountering patients with MD-like symptoms, the current findings suggest that a structured occlusal evaluation (including T-Scan and EMG when available) may be warranted as part of a multidisciplinary diagnostic workup. Where occlusal disharmony with prolonged DT and associated masticatory hyperactivity exist, measured DTR performed under digital guidance and with conservative tooth modification may be considered as an adjunct before undertaking irreversible otologic procedures. Important practical notes:

-

DTR should be performed only after appropriate training and with documented digital verification.

-

Discuss the nature of DTR for MD-related symptoms with patients and document informed consent specifically addressing potential benefits and risks.

-

Record and report objective metrics (DT, EMG, JVA) to aid future evidence synthesis. Any provider considering MD as a working differential diagnosis should eliminate TMD as a possible (probable) diagnosis before accepting a diagnosis of Meniere’s Disease.

CONCLUSION

This study demonstrates a strong association between occlusal dysfunction and the clinical presentation of Ménière’s disease in patients who had previously been cleared of auditory neuromas through MRI evaluation. All patients exhibited prolonged occlusal disclusion times, highlighting a common functional abnormality prior to intervention. Following occlusal corrections guided by T-Scan and EMG biometric data through Disclusion Time Reduction (DTR) Therapy, patients experienced measurable improvements across multiple objective and subjective parameters. Symptom intensity, duration, and frequency were notably reduced,29 while mastication analyses revealed significant enhancements in muscle physiology, chewing velocity, and movement patterns.30 Additionally, Joint Vibration Analysis showed substantial reductions or complete resolution of pathological joint sounds, accompanied by increased range of motion.31 Collectively, these findings suggest that data-driven occlusal correction via DTR Therapy played a meaningful role in improving neuromuscular function, temporomandibular joint health, and symptom burden in this patient population, warranting further investigation into its therapeutic potential as well as the true etiology of MD.

Taken together, the findings of this four-part study suggest a compelling reinterpretation of the relationship between Ménière’s disease and temporomandibular disorders. The successful use of DTR indicates that the symptomatology attributed to MD may originate from undiagnosed or improperly managed TMD. The high degree of clinical improvement observed following data-guided occlusal correction challenges the assumption that these patients’ symptoms were primarily otologic in nature. Instead, these results raise the possibility that MD may be misdiagnosed in a subset of patients whose underlying condition is biomechanical and neuromuscular dysfunction of the masticatory system. Further controlled studies are warranted to clarify diagnostic overlap, refine differential diagnostic protocols, and determine the extent to which TMD-focused therapies may offer effective, noninvasive treatment alternatives for patients presenting with MD-like symptoms.

Funding Statement

No funding or in-kind value was received for this project.