INTRODUCTION

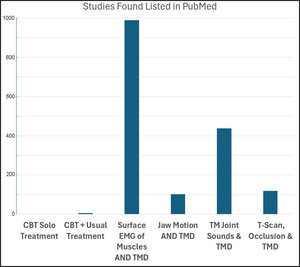

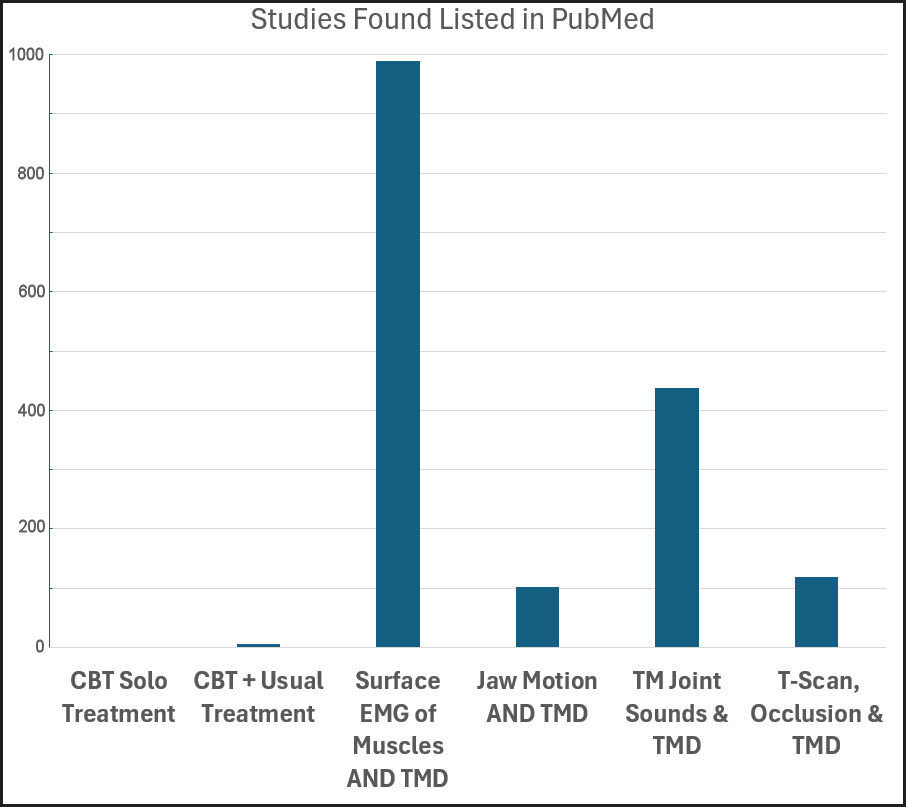

A recent publication signed by 30 dentists offered their collective opinion related to diagnosis and treatment entitled: Temporomandibular disorders: INfORM/IADR key points for good clinical practice based on standard of care.1 However, it is likely that most practitioners currently experiencing success in treating TMDs can see the obvious inconsistencies within their suggestions. This group of suggested points indicates a belief that TMDs can never be cured or even corrected, but that practitioners can only manage painful symptoms. Thus, the definition of success must be limited to any reported reduction in pain. Greene has campaigned for decades against accepting any physical etiology for TMDs ever since he and Laskin proposed the Myofascial Pain Dysfunction Syndrome (MPDS) theory in 1969.2 The MPDS theory remains unsupported scientifically today 56 years later. Greene and cohorts have also actively and continuously campaigned against all modern diagnostic measurements and treatment technologies during the past four decades.3–8 They have been promoting their opinion of a biopsychosocial etiology for TMDs combined with advocating for an anti-technology approach to both the diagnosis and treatment of TMDs. Some of those most adamantly opposed to acknowledging any physical etiology for TMDs and/or the use of modern measurement technologies previously participated in unsuccessful efforts to validate the RDC/TMD and its psychosocial claims. See Figure 1. The RDC/TMD cannot accurately diagnose TMDs (with acceptable sensitivity and specificity) by using only the patient’s medical history and clinical examination findings. Also, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) has never been shown to be an effective stand-alone treatment for TMDs.9

Evidence of an ongoing political campaign rather than a contribution to dental science

The aforementioned 10 Key Points article was originally published in CRANIO, a closed access journal. However, the authors were not satisfied to present their opinions following usual scientific procedures, so they have subsequently published the same opinions in three additional journals (See addendum), two of which are Open Access to increase dissemination. Next, they sent letters to editors of dental journals around the world asking them to promote their 10 Key Points.

Understand that these 10 Key Opinions of this small group are without substantial scientific support and that they have chosen to ignore decades of real scientific support for biometric instrumentation (EMG, Jaw tracking, T-Scan, etc.). In addition, this group has failed to provide any scientific evidence that the use of biometric instrumentation cannot be used successfully with respect to TMDs. The one author whose name appears in all five publications is Daniele Manfredini, the apparent group leader.

Further evidence that this activity is a political campaign rather than a scientific treatise is plain in the variety of authors. In the Polish language publication, a new group of authors was recruited with only Manfredini remaining from the original CRANIO list. Thus, it is unlikely that any of them participated substantially in its production. For the American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics version only Manfredini and a completely new author were listed. At a minimum this is an extremely unethical approach.

The use of the scientific method

Scientific dental research requires the use of the scientific method,10 which states that the purpose of research is to test and attempt to DISPROVE every new theory, not to attempt to “VALIDATE” it. In other words, a scientific theory is considered valid only as long as it has not been refuted by new evidence. A scientific theory cannot be validated but only provisionally accepted until disproven. (The RDC/TMD was disproven even by the promoters of it.) This means that scientific knowledge is always tentative and must remain open to rigorous attempts at falsification. Even a single contradictory observation is enough to overturn or force modification to a scientific theory. Science progresses through successive testing and refutation rather than validation. E.g., When Disclusion Time Reduction (DTR) treatments have repeatedly been used with T-Scan/EMG to eliminate all painful TMD symptoms and also reduce or eliminate patient’s moderate to severe depression, it does not prove that occlusion is the universal etiology of TMDs.11 However, it supports that occlusion is one etiology of TMDs, and that the apparent Somatic Symptom Disorders (SSDs) commonly associated with TMDs can be secondary to chronic physical pain. To disprove a scientific theory, it is only necessary to reveal one failure of it, but it is never possible to prove a scientific theory.12 The dental profession should stop looking for the one etiology of all TMDs, as well as one single universally effective treatment. It is true that NSAIDS can be prescribed for nearly any muscular pain condition (if the patient is not allergic), but NSAIDS never correct the underlying etiologies of most TMDs.

OBJECTIVES

The first aim of this review was to request an evaluation of these 10 Key Points for the diagnosis and treatment of TMDs from fifty-three very successful TMDs treatment providers. Secondly, a literature review was undertaken to consider whether these Key Points have any credibility as a Standard of Care for the diagnosis and treatment of TMDs. A group of fifty-three currently practicing TMDs providers that have successfully treated thousands of TMDs patients agreed to contrast their diagnostic and treatment methods with these 10 Key Points.

METHODS

The responses of the fifty-three TMDs practitioners were analyzed statistically for their percentage of agreement/disagreement with the 10 Key Points. Then, a critique of each recommendation was separately developed citing dental literature that either supports or contradicts each key point. In some areas the literature was thin because some demonstrably false notions are still being taught, such as the concept that articulating paper marks can be accurately interpreted in terms of occlusal contact forces.13–16 A review was then produced regarding facts that are overwhelmingly supported within the literature; 1) the use of surface EMG, 2) Jaw Tracking and 3) other modern computerized technologies that enhance the accuracy of diagnoses and treatment planning for TMDs. A review of T-Scan implementation that precisely and with minimal invasiveness selectively removes interfering contacts in occluso-muscular TMDs was also performed.17 This review of T-Scan was used to demonstrated the value of outcome measurements for efficacious treatment of occluso-muscle TMDs.

THE TEN KEY POINTS

Key Point 1.

“Patient-centered decision-making alongside patient engagement and perspective is critical to manage TMDs, with management being the process from history through examination into diagnosis and then treatment. Expectations should focus on learning to control and manage the symptoms and decrease their impact on the individual’s everyday life.”1

There is much agreement with the concepts of patient-centered and patient engagement. However, the authors are suggesting that no temporomandibular disorder is ever curable, and that TMDs are usually mysterious conditions without any knowable etiology other than somatization. The readily available scientific literature has repeatedly revealed that pursuing a diagnosis limited to only the patient’s history and clinical examination findings has consistently resulted in an unacceptably high percentage of misdiagnoses.18–20 Even Greene previously admitted that clinical diagnoses of TMJ internal derangements can produce a false negative rate of 35 % (missed) combined with a false positive rate of 25 % (normal joints).21 One must ask, is it conscionable to “throw in the towel” and assume that all TMDs can only be “managed” when that is likely true for only a small percentage of the cases? A more likely KEY to TMDs treatment success is 1) pursuing the most accurate diagnosis possible and then 2) designing the most appropriate individualized treatment together with the patient’s understanding and agreement.22

When all the patient’s symptoms are immediately eliminated after functional occlusal interferences are removed (not just the bite “feeling a little better”), it is either the world’s most magnificent placebo effect (which is highly unlikely) or the occlusal treatment actually resolved that patient’s occluso-muscular temporomandibular disorder.17 TMDs often include a musculoskeletal dysfunction, (see recommendation 2), which should be an obvious reason to objectively measure that level of dysfunction, but no mention of that is included anywhere within these 10 Key Points.

Although the symptoms associated with TMDs often include painful muscles, they do not usually include either neuropathy or myopathy (systemic muscle or nerve disease). Thus, the muscular symptoms are found by many providers to be secondary to structural abnormalities such as:

a.) Malocclusion,23

b.) Internal derangements of the TMJs,23

c.) A developmental, iatrogenic or traumatic maxillo-mandibular mal-relationship.23

This is the explanation for why the painful muscular symptoms can be routinely relieved either by a careful Disclusion Time Reduction (DTR) occlusal adjustment, or with an oral appliance, which are the 2 most popular and highly successful TMDs treatments.24 It is curious that although these 10 Key Points authors acknowledge that TMDs are musculoskeletal dysfunctions, they seem adamant that the measurement of any dysfunctions should be avoided. Measuring dysfunction is not only helpful for discerning a more accurate diagnosis, but post-treatment measures can objectively reveal the extent of any successful reduction in the patient’s dysfunction.25

Key Point 2.

“TMDs are a group of conditions that may cause signs and symptoms, such as orofacial pain and dysfunction of a musculoskeletal origin.”1

The authors are to be congratulated for recognizing the diversity of TMDs and acknowledging that it should always be referenced in the plural form. Orofacial pain is the least descriptive term describing TMDs, especially with no specific location and no ability to objectively quantify it in absolute terms. Consequently, those providers focused solely on “orofacial pain” as the only important symptom, tend to prescribe palliative management solutions rather than seeking to correct or eradicate any etiological factors. Pain is a subjective opinion of the patient, and although it indicates there is something wrong, pain does not often reveal its etiology. By itself, pain offers little to no insight for selecting an efficacious treatment, thereby relegating treatment selection to trial and error. Most dysfunctions can be identified, measured and compared to known good functions. However, since the promoters of these Key Points are apparently opposed to all objective functional measurements, they are unwilling to measure dysfunction or compare those measurements to known good function as an outcome measure.

Key Point 3.

“The etiology of TMDs is biopsychosocial and multifactorial.”1

It is unscientific to accept a diagnosis of Somatic Symptom Disorder (SSD) at the initial visit because the symptoms of SSD are not distinguishable from those produced by physical etiologies. For the same reason, the assumption of social stress as the etiology of all TMDs is unthinkable. It is a standard practice in psychiatry to eliminate the presence of physical etiologies before considering a diagnosis of SSD.26 If TMDs were SSDs, psychologists and psychiatrists should today be the primary providers of TMDs care and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) should be a very popular TMDs treatment. However, they are not, and CBT is not. See Figure 2.

The scientific evidence supporting any psychosocial etiology of TMDs is embarrassingly minimal and psychologists successfully treating TMDs are exceedingly rare. However, dentists successfully treating TMDs patients using physical methods are most common. While it has been shown that many TMDs patients do suffer from depression and/or anxiety due to their long-term chronic intractable pain, it has been shown conclusively that the emotional aspects are secondary to the pain, not etiologic of TMDs.11,25 If depression and/or anxiety were the real etiologies of TMDs, CBT counseling and/or antidepressive medications should be expected to effectively and successfully relieve all TMDs symptoms but neither has been effective. There has been minimal scientific testing of the efficacy of CBT as a treatment for TMDs. In fact, no study has found that CBT by itself can be an efficacious treatment for TMDs. See Figure 2. Combining CBT with “usual TMD treatment” or “standard TMDs treatment” has only resulted in temporary limited improvement in coping ability, even when mild TMDs cases were purposely selected.27,28

Since there are at least 40 different conditions associated with TMDs, certainly some cases can be regarded as multifactorial, but not all cases are. Many decades ago Okeson astutely observed, “…the most important prerequisite to selection of a treatment method is an understanding of the etiology of the problem.”22 It is a common understanding that TMDs can sometimes result mainly from a single factor such as a TMJ internal derangement,29 or a malocclusion,30 so determining the exact etiology of a specific TMD can be a critical step for selecting an appropriate corrective treatment. However, a TMDs case with a single structural deficit can adversely affect the entire masticatory system, creating muscular pains, headaches, sleep deprivation, stiff neck, and/or many other symptoms, creating the appearance of a multifactorial etiology.

The term “multifactorial” when applied to TMDs, suggests there must be many physical etiologies for TMDs and it is true that some patients have multiple etiologies. Multifactorial does not suggest or imply that all TMDs patients have multiple etiologies for their painful conditions. E.g. A patient with a high filling or crown and no other etiologies, may be completely resolved of multiple TMDs symptoms after a precise occlusal correction. These authors even acknowledge this common phenomenon in their Key Point 9.

Misconception results from the unscientific belief that TMDs are Somatic Symptom Disorders (SSD), the current psychiatric term for somatization (illness behavior), and the assumption that no significant physical factors are worthy of discovery.11,25,26 (See discussion of Key Point 8) It follows the nonsense promulgated by some authors that all internal derangements will eventually self-heal, and that most patients can adapt over time to any type of malocclusion, or even a malformed maxillo-mandibular relationship.7

Key Point 4.

“Diagnosis of TMDs is based on standardized and validated history taking and clinical assessment performed by a trained examiner and led by the patient perspective.”1

This may be the most disturbing fallacy of this published treatise. That is not to say that the patient’s history and a careful clinical examination are not necessary, not useful or should be dispensed with. However, the medical history and clinical examinations are routinely inadequate for an adequate diagnosis of TMDs, and no patient should be expected to provide the clinician with a complete and precise diagnosis. In 1990 Dworkin et al., questioned the reliability of using clinical signs stating, “…many clinical signs important in the differential diagnosis of subtypes of TMD were not measured with high reliability.”31 However, the same author subsequently invented the Research Diagnostic Criteria for TMD (RDC/TMD) using only the history of symptoms and limited clinical signs to diagnose TMDs.32 The results of their 1.5 decades of careful studies invalidated Axis I of the RDC/TMD for its intended purpose (obtaining physical diagnoses) due to unacceptably low sensitivity and/or specificity. However, it did prove scientifically that using just the Axis I history and clinical exam findings of the RDC/TMD will be inadequate to diagnose too many TMDs physical etiologies. While Axis II uses accepted devices to assess emotional states, doing so without first addressing physical etiologies is contrary to standard psychiatric methods.

The act of discouraging the use of modern technology is counter to common sense when dental science has clearly demonstrated the inadequacy of relying on just the history and clinical exam to diagnose TMDs. In one study, 29 % of 422 clinical diagnoses of internal derangement were found to be false positive by MRI suggesting a specificity of only 71 %.19 In another study, clicking and pain in the TMJ helped identify only one half of 51 patients with abnormal condyle-disk relationships that were subsequently detected with MRI.20 In a study of 110 patients comparing clinical diagnoses to MRI, agreement occurred only with 43 % of the joints (sensitivity of 69 % and specificity of 51 %), and when there was agreement regarding the presence of an abnormality, 50 % of the time the clinical diagnosis incorrectly staged the abnormality.18 Thus the accuracy of relying just on the history and clinical examination can be as low as 25 %, even with “experienced clinicians.” One author of these recommendations (Greene) has even previously published a study revealing 35 % false negative combined with 25 % false positive results (55 % incorrect) when a combined history and clinical examination diagnoses were compared to MRI.21

A missed diagnosis or a misdiagnosis (wrong diagnosis) can lead to a poor choice of treatment or no treatment, and ultimately a lack of success, or even iatrogenic worsening that some authors (Greene & Manfredini) refer to as chronification.8 This again emphasizes that achieving an accurate diagnosis before selecting any treatment must be the crucial step towards routine long-term success.33 It is likely that the unnecessary limitation of using only the history and clinical exam findings to develop TMD diagnoses greatly increases the probability of chronification, due to the increased likelihood of implementing either, inappropriate, ineffective or no treatment. Note: A question arises whether this group of authors have experienced such terrible results and/or chronification that they have become very negative towards any newer TMDs diagnostic techniques and physical treatments.

Key Point 5.

“Imaging has been proven to have utility in selected cases but does not replace the need for careful execution of history taking and clinical examination. Magnetic Resonance Imaging is the current standard of care for soft tissues and Cone Beam Computerized Tomography for bone. Imaging should only be performed when it has the potential to impact the diagnosis or treatment. Timing of imaging is important and so is the cost-benefit-risk balance.”1

This Key Point recognizes the potential contribution of imaging to an accurate TMDs diagnosis and is now included within the DC/TMD. However, it claims that before deciding to obtain any imaging, (typically MRI or CBCT), the clinician must anticipate how the resulting image(s) will improve the diagnosis and/or how it will lead to a more effective treatment. This is a Crystal Ball requirement. Only an imaginary Crystal Ball could produce that information prior to taking the images. It is a fact that if the practitioner always knew in advance what imaging would reveal, it would never be necessary to take any images. The purpose of imaging is not to replace history and examination, but to add knowledge to what has already been learned from them, and from many other available inputs. This Crystal Ball recommendation (key point 5) lacks common sense and must be entirely disregarded in TMDs clinics. While the cost and risk of imaging can be estimated in advance, the benefit of an image for a given patient cannot routinely be predetermined.

Key Point 6.

“The evidence base for all interventions or devices should be carefully considered before their implementation over and above normal standard of care. Knowledge on developments in the field should be kept up to date. Currently, technological devices to measure electromyographic activity at chairside, to track jaw motion, or to assess body sway, amongst others, are not supported.”1

How much scientific support is enough? There are a few Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) studies showing minimal TMDs treatment effect even when added to "usual TMD treatment" (that being appliance therapy), and zero studies using CBT alone as the sole TMDs treatment. See Figure 2. Every other TMDs treatment approach overwhelmingly beats CBT in terms of evidence-based scientific support. The minimal published evidence promoting MPDS as a psychophysiological disorder that is marked by depression and somatization was apparently conjured, rather than being scientifically produced since it has never been replicated.34,35 It is well-known that Psychiatry as a profession, only accepts a somatization diagnosis (currently termed Somatic Symptom Disorder), after all possible physical causes have been diagnostically eliminated. The reason physicians have coined the term biopsychosocial rather than psychosociobiological is because they understand that biology must come first.26

This recommendation to avoid technology in the diagnosis and treatment of TMDs must result from an inability or an unwillingness of these authors to read the dental technology literature. There are 7,560 published scientific studies/reviews of jaw tracking listed by Google Scholar, which is the most complete listing service when searching Jaw Tracking AND TMD. Of these PubMed lists only the top 102 studies. Consider that 102/2 (Jaw Tracking to CBT) is still a very large ratio. Jaw Tracking has a five decade use history in evaluating TMDs, and represents the best, most practical and objective method for evaluating masticatory dysfunction.36–44 Mastication (chewing) is a human survival function such that Dental Medicine should logically be the profession responsible for maintaining good masticatory function. Further, by adding simultaneously recorded surface EMG to Jaw Tracking, a greater measure of masticatory functional quality can be diagnostically obtained.38–40 Since dysfunction is half of these authors’ definition of TMDs (Key Point 2), the measurement of temporomandibular dysfunctions should be an obvious step towards understanding the patient’s condition.

PubMed lists 101,000+ published studies utilizing EMG. More specifically, searching “EMG AND Temporomandibular Disorders” revealed 994 published studies evaluating surface electromyography’s efficacy in the diagnosis of stomatognathic muscle dysfunction. Ironically, some of these key point authors have published their own claims that EMG is efficacious in measuring muscular dysfunction, especially in detecting the presence of and extent of Awake Bruxism (AB),45–48 and in validating orthodontic aligner efficacy.49 Some of these same key point authors found statistically significant differences in muscle activity recorded from TMDs subjects and controls, stating “temporomandibular disorders patients showed different muscular recruitment patterns compared to controls.”48 Since EMG has been established over the past 70+ years as a reliable method for research studies, how is it not reliable for use in clinics? With modern technology it is rather quick and easy to produce reliable data.

Key Point #6’s claim of no support for electromyographic diagnostic technology is in stark conflict with the fact that some of these authors’ claims regarding EMG efficacy have been stated in their own studies. Despite some key point authors publishing multiple EMG studies, these same authors deny EMG should be used when evaluating TMDs. Have the authors decided their own publications are wrong? Have they just forgotten their own previously published conclusions? Or did some of the authors not read all 10 Key Points carefully before signing up to be a key point author?

This Key Point suggestion that computer technologies have insufficient scientific support in the present day is ludicrous, making this recommendation nonsensical. Was it perhaps made to intentionally misrepresent the status of today’s TMDs-related computer technologies? The research-supported reality is that multiple technologies can accurately capture TMDs dysfunction, which has led to more effective TMDs diagnoses and treatments being implemented in countries worldwide. E.g., The T-Scan 10 computerized technology has revised the understanding of occlusion and has completely cast aside the concept that articulating paper marks can be used to determine the forcefulness of contacts.13–16

Key Point 7.

"TMD treatment should aim to reduce the impact of pain and decrease functional limitation. Outcomes should be evaluated also in relation with the reduction of exacerbations, education in how to manage exacerbations, and improvement in quality of life.1

While pain may be temporarily reduced with pharmaceuticals, how can it be determined if any functional limitations have decreased without measuring them? The vertical Range of Motion is only one factor affecting the quality of masticatory function such that when an obvious functional limitation disappears completely (e.g., a closed lock opens wide) that may be easily recognized, but their statement implies that smaller incremental changes, presumably not obvious to an observer, could lead to improvements in quality of life. Objectively measuring subtle functional limitations detects smaller incremental improvements not visible to the pracitioner.37–44 This Key Point suggests that the main objective is to not make the patient’s condition worse (exacerbated), which is the authors’ rationale for limiting treatment to reversible options. Since the key point authors’ diagnostic approach is solely based upon the history and examination, their diagnosis must often be doubtful, as would be any follow-on treatment approach. Using a Trial-and-Error approach requires reversibility to allow the practitioner to withdraw treatments that fail when symptoms don’t improve or worsen (chronification). This key point is only rational when a practitioner does not obtain a precise diagnosis and consequently, is unable to formulate an effective treatment plan.

Alternatively, some TMDs can be successfully treated with reversible methods (e.g., using a temporary splint followed by weaning), but many TMDs require permanent, irreversible treatments. There is no logical reason to claim that “a one-size-fits-all approach” will achieve success in 40 different TMDs types.22 TMDs treatment providers who achieve a precise diagnosis can select the most appropriate treatment, either reversible or irreversible with an expectation of success.50,51 Incidentally, most dental procedures are irreversible, and that is not considered a problem. Moreover, it has been shown that splint use is not as reversible as previously advocated, inducing changes within the temporomandibular joints and the occlusion within just a few months.52 Because some TMDs patients can be successfully treated without irreversible methods, it cannot be assumed that all TMDs patients can be treated successfully using reversible methods. And patients who were treated successfully with irreversible methods cannot be assumed to have been treated equally as successfully using reversible methods.11,25,50 The only reasons for advocating reversibility are a lack of confidence in treatment efficacy, or overconcern for some imagined treatment risks.

Key Point 8.

“TMD treatment should primarily be based on encouraging supported self-management and conservative approaches, such as cognitive-behavioral treatments and physiotherapy. Second-line treatment to support self-management includes provisional, interim, and time-limited use of oral appliances. Only very infrequently, and in very selected cases, are surgical interventions indicated.”1

Liang Q et al., in their systematic review found 5 CBT studies related to TMDs, 2 of B and 3 of C category quality.53 Their conclusion was, “the methodological qualities of included studies on CBT on TMD are generally low, and its reporting quality which is checked by CONSORT is also unsatisfactory.” Key Point 8 suggesting cognitive behavioral therapy as a primary therapy has zero scientific credibility for resolving TMDs.27,28 In a recent Systematic Review of 22 RCTs that used psychological therapies for TMDs, the authors concluded “overall, we found insufficient evidence on which to base a reliable judgement about the efficacy of psychological therapies for painful TMD.”54 In another systematic review of the management of sleep bruxism in adults, the authors concluded “…the potential benefits of CBT were not well supported.”55 And in another recent study, behavioral therapy compared unfavorably to occlusal appliance therapy (p < 0.001), at least in large part because 75 % of the subjects dropped out of the behavioral therapy.56 A dropout rate of 75 % should be a clear message to the providers that the patients were not experiencing benefits. Further, no scientific publication has revealed a successful treatment strategy using CBT alone. The most that can be attributed to CBT is that when used in conjunction with “standard” or “usual” TMD treatments (splints, medications), coping skills may be improved in unsuccessfully treated patients who typically remain affected by painful symptoms.

Of note is that TMDs patients often take exception to a dentist’s quick referral for mental health counseling.

If self-management was effective, TMDs patients would not need to be treated by any practitioner. Just send the patient home with a list of suggested actions and/or inactions. A recent publication testing 7 self-treatment online apps found little support for using self-treatment. The 7 apps were scored poorly for both engagement (2.71/5) and for information (2.92/5).57

CBT is used routinely by psychiatrists 1) for real Somatic Symptom Disorders cases, but only after determining that all possible biological etiologies are absent, or 2) in terminal cancer cases to improve coping when no biological treatment has been successful. CBT is designed to improve coping skills in patients with SSD or chronic intractable pain, not to cure or correct any masticatory dysfunctions.

In stark contrast, when patients had their emotional status tracked with the Beck Depression Inventory II during physically successful TMDs treatments, patients benefitted greatly as their depression levels reduced from moderate and severe down to normal.11 The question of whether Somatic Symptom Disorders are a common etiology of TMDs was negatively answered when PHQ-15 scores were likewise reduced from a mean of moderate severity to a mean of normal emotional status, after physical corrections dramatically reduced or eliminated all TMDs symptoms.25

These 10 Key Points authors published a prime misconception example that TMD has a psychological etiology because at intake, 44 % of 691 TMD patients presented with severe depression (SCL-DEP) and 51 % presented with severe or 23 % moderate somatization (SCL-SOM). The authors concluded that “patients with TMD frequently present an emotional profile with low disability, high intensity pain-related impairment, and high to moderate levels of somatization and depression…”58 These false positive diagnoses were made prior to any “usual” physical TMDs treatments being utilized to relieve subjects’ high intensity pain. The observed depression and perceived somatization levels were likely secondary to the subjects’ chronic pains, and could be expected to dramatically decrease with a successful physical treatment, but not with CBT alone.11,25 According to Sam Dworkin, the father of the RDC/TMD, “True somatization disorder is very rare (< 1%) and requires a DSM-III-R diagnosis including at least 13 different physical symptoms which cannot be explained by, or are in gross excess of physical findings, and have caused patients to seek health care or alter their lifestyles.”59 This suggests that pre-testing all TMDs patients for somatization (SSD) using PHQ-9 and anxiety using GAD-7 (as has been recommended by the American Academy of Orofacial Pain) prior to patients undergoing appropriate physical treatments will be likely to produce a large percentage of false positive diagnoses of heightened anxiety and/or somatization (SSD), as well as being a gross waste of clinic time.

A recent physiotherapy self-management home-exercise TMD treatment literature review authored by Michelotti (one of the 10 Key Points’ repetitive authors) reported that “…evidence for the efficacy of home physical exercises is weak because of the very limited number of randomized clinical trials (RCTs) available in literature.”60 Thus, Key Point 8’s recommendations promulgate a treatment approach with minimal science supporting it, while denigrating other techniques strongly supported by myriad scientific studies. See Figure 2.

Key Point 9.

“Irreversible restorative treatment or adjustments to the occlusion or condylar position are not indicated in management of the majority of TMDs. The exception to this may be an acute change in the occlusion, such as in the instance of a high filling or crown with TMD-like symptoms developing immediately following these procedures or a slowly progressing change in dental occlusion due to condylar diseases.”1

Fillings, crowns, orthodontics, endodontics, prosthodontics, oral surgery and implantology are all common irreversible dental treatments that dentists provide to patients every day. A common reversible treatment in general dental practice is the fully removable denture, but only if provided without any soft tissue management, which is not usually the best approach. Because it is universally understood that a high filing or crown can immediately cause TMD-like symptoms, it is absurd to even suggest that occlusion can be absolved from any involvement in TMDs. High fillings and crowns are very common, and the judicious provider will adjust them at delivery. Occlusion as an iatrogenic factor precipitating TMDs may be nearly as common as high fillings, crowns, bridges, and/or adult orthodontic treatments. Also, the absence of molars/premolars can also contribute etiologically to TMDs, while their implant supported restorations are definitively irreversible treatments.

The true value of TMDs treatment reversibility is realized when a wrong treatment choice exacerbates the symptoms (See claim #7 above), which may occur from an inaccurate (or lack of) understanding of the condition’s etiology prior to initiating treatment. Thus, the importance of obtaining an accurate diagnosis cannot be overstated.

Reversibility may be useful for practitioners using a trial-and-error approach to treatment, such that after a negative response they can back out and try something else. Key Point 8 acknowledges that oral appliances have been used for decades, being the most widely accepted TMDs treatment. Key Point 8’s admission that oral appliances “are useful” suggests an admission by these authors that physical factors are widely present in many TMDs. Since oral appliances are known to be effective for TMDs and CBT is not, that substantially reduces the likely presence of a psychosocial etiologic component to the 1 % level that psychiatry has acknowledged previously.

Key Point 10.

“The presence of complex clinical presentations with uncertain prognosis, such as in the case of concurrent widespread pain or comorbidities, elements of central sensitization, long-lasting pain, or history of previous failed interventions, should lead to the suspicion of chronification of TMDs or non-TMD pain. Referral to an appropriate specialist is thus recommended; the specialty will be geo-graphic-specific as not all countries have a specialty of orofacial pain.”1

“Chronification” is a term coined by Manfredini & Greene to refer to the process of change from acute to chronic, due to a lack of treatment, inappropriate treatment, or just unsuccessful treatment (potentially iatrogenic).8 They acknowledge “The anatomy and pathophysiology of muscles, joints, disc and nerves may all be involved in predisposing to TMD symptoms, especially when the patients have pain elsewhere in the body.” However, they also claim “Among the psychosocial factors, some features may be elucidated by the DC/TMD axis II, while others (eg illness behaviour, Munchausen syndrome, lack of acceptance of non-mechanical approaches) require careful evaluation by trained clinicians.” Blaming the lack of acceptance of non-mechanical approaches, presumably by the patients is nothing more than a rationalization for the failures of CBT.

Although some TMDs patients have multiple factors affecting their symptoms, many have one primary factor, which when dealt with effectively eliminates or lowers the painful symptoms to a tolerable or absent level.11,17,61–65 Every diagnostic effort that affords a more complete understanding of the underlying problem(s), leading to a more appropriate treatment(s) selection provides longer-lasting symptom relief by correcting or minimizing the underlying physical etiology(s).

The natural process of transitioning from an acute condition to a chronic one is the body attempting to adapt to a new trauma or condition. This adaptation automatically proceeds unless a treatment initiates to either stop or facilitate the adaptive progression. An injury either heals or becomes chronic. A majority of TMDs patients are chronic with years of adaptation behind them. Some lucky, highly adaptive individuals successfully adapt to an internal derangement and can redevelop good TMJ function, despite a permanent derangement. However, less adaptive individuals will suffer from instability and possible degenerative joint disease over time. The ability to assess the level of successful adaptation of a TMDs patient with technology-based biometric functional visualization is invaluable.

The hypothesis of Central Sensitization (CS) lacks distinct symptom characteristics that would precisely identify CS when patients present with identical symptoms arising from local physical etiologies. Therefore, CS often becomes a default diagnosis within a process of elimination, when no clear alternative diagnosis has been identified. No evidence has been produced to support that CS results from just emotional factors.

DISCUSSION

The proposed restriction to limit diagnostic data solely to patient history and clinical examination while purposefully avoiding objective or measured inputs suggests that a precise TMDs diagnosis is not valued. Limiting treatments to reversible, noninvasive interventions suggests a trial-and-error approach towards poorly diagnosed conditions with an expectation that failures will require reversal.

The authors’ claim of biopsychosocial etiology for TMDs lacks adequate scientific literary support, which has alternatively supported 40+ physical (biological) etiologies. Emotional distress from an outside source is unlikely to cause TMDs, but may in some cases exacerbate the symptoms because a true diagnosis of somatization (Somatic Symptom Disorder; SSD in psychiatry) is very rare (< 1 %).59 Consequently, applying the PHQ-15 or PHQ-9 to physically untreated TMDs patients is likely to produce rampant false positive SSD diagnoses or significant exaggeration of conditions (a mild condition labeled as severe) in up to 99% of cases.25 Successful physical treatment of TMDs routinely reduces or eliminates the emotional factors to acceptable levels dramatically enhancing the quality of life.

The suggestion that a provider should be able to anticipate what information an MRI or CBCT image will contribute to a TMDs diagnosis or a treatment outcome prior to ordering the imaging lacks ordinary common sense.

Their recommendation that practitioners keep up to date with the latest TMDs diagnostic and treatment knowledge is truly ironic. Most of these key point authors ignore the past 3+ decades of effective TMDs treatments and openly denigrate decades of technology-based advancements in techniques for diagnosing and treating TMDs. Instead, they promote decades-old, unsupported, and unscientific opinions.

What are the standards of care within the world’s population of TMD providers?

Temporomandibular Joint Sounds

It is universally acknowledged that TMJ sounds are indicative of abnormal internal derangements, often clearly identifying a precise diagnosis, while at a minimum, encouraging a diagnostic inquiry.66 Recording TMJ sounds with Joint Vibration Analysis (BioJVA, BioResearch Associates, Inc. Milwaukee WI USA) can in a few minutes and at minimal cost determine if a TMJ is normal or not with a specificity of 98%,67 and indicate whether an MRI or CBCT will likely provide more diagnostically useful information based upon the presence or absence of degenerative vibrations. Consequently, JVA is a technology that partially fulfills their Crystal Ball requirement.68–70 And, recorded joint sound intensities and frequencies can be quantitatively preserved to objectively compare between pre-treatment to post-treatment as an indication of outcome efficacy. Since TMJ sounds are universally considered TMDs symptoms it makes no sense to argue that some symptomatic subjects have joints sounds too. NOTE: Since a “clicking joint” is universally considered a TMDs symptom, there can be no such thing as asymptomatic clicking even when pain free.

The consensus is that a quiet TM joint with normal Range of Motion (usually > 40 mm) can acceptably function, even with a permanent disc displacement.71 Sometimes the JVA trace of a well-adapted, good functioning internal derangement can be a permanent diagnostic record that eliminates the need for further imaging, or for the initiation of unnecessary TMJ treatment. JVA data from these unusually well-adapted TMDs can even satisfy their spurious Crystal Ball requirement (Key Point 5 above). Numerous technologies, instruments and methods are commercially available to record and process joint sounds (e.g., an electronic stethoscope or a doppler device) and have been used for decades.

Imaging

Imaging can determine in detail the existing abnormalities within a damaged/diseased TM joint, including the disc position, existing inflammation or effusion, skull base bone loss, any condylar resorption, changes in joint morphology, presence of cysts or tumors, and a reduced ramus height. However, it is not cost-effective to image normal or well adapted joints with good function. Once a precise diagnosis has been established, a competent practitioner can decide whether treatment is indicated, and what may be the best intervention with maximum benefit and the least risk. It cannot be overstated that without imaging a dysfunctional TM joint, an unreliable diagnosis may be accepted and the treatment of that structurally compromised joint may devolve into guesswork.18–20 The objective of thorough structural diagnosis is the overall goal to have the patient and clinician understand the status of a critical element within the biological system (the TMJ). Common conditions revealed through imaging may explain the etiology or affect treatment decisions regarding definitive care and/or a treatment’s prognosis,

Jaw Tracking

In addition to evaluating TMJ pain, functional TMJ assessments with Jaw Tracking can be performed prior to joint imaging. Measuring masticatory dysfunction when present, precisely maps the dysfunctional motion patterns, and documents improvements recorded after treatment. TMDs patients with moderate masticatory dysfunction usually are unaware of their condition, but Jaw Tracking may indicate the patient has a preferred chewing side, difficulty swallowing, or becomes tired with sore muscles during or following chewing. A severe masticatory dysfunction may result from missing posterior teeth and include signs like rampant occlusal wear. Any present clinical signs and symptoms may (or may not) illustrate the specific dysfunction’s etiology or reveal a needed corrective action. However, analyzing chewing movements with the Kinesiometric Index72 provides insight into the extent that present structural problems exist and can contribute to the development of a treatment plan. When an objectively measured improvement towards chewing normalcy has been recorded post-treatment, the degree of treatment success achieved can be objectively revealed.

Electromyography

Electromyography (EMG) is a well-established technology that many of these key point authors have used in their own research. If it is reliable for research, it is also reliable for clinical purposes, especially when the clinician understands what is being described by EMG data. Muscle pains are the most common complaints from TMD patients, and no other diagnostic method exists that can objectively evaluate muscle function. Palpation may detect the presence of muscle pain, depending on how much force is used in the palpation and how sensitive the patient is. But palpation as a screening test alone will not reveal any physiological etiology for the muscular TMDs diagnosis. Painful muscles under palpation indicate EMG testing will very likely contribute to the diagnosis and treatment of a TMDs case.

EMG can also be employed simultaneously with jaw tracking to evaluate muscle function during chewing, providing the ultimate evaluation of the quality of overall masticatory function.73–76 Normal masticatory function as well as adapted muscle function are both easily recognized. Poor masticatory function (or dysfunction) is a continuum, extending from slightly compromised to terrible, such that a patient’s level of dysfunction can be determined anywhere throughout that continuum. Incremental improvements can be objectively documented from post-treatment records.

T-Scan – Disclusion Time Reduction vs. Articulating Paper Marks

When malocclusion is present it, has been definitively proven that dentists are incapable of reading articulating paper marks to find the nature of that malocclusion, compromising a clinician’s efforts to accurately remove interfering contacts and/or excessively forceful contacts.14,15,77–80 Conventional paper mark adjusting is not accurate enough to eliminate the human occlusal neurophysiology that causes many common TMDs because ink markings and Shimstock pull, foil, silk ribbon, intra-oral scanners and holes in occlusal wax do not measure occlusal contact forces at all.13,81 But 256 occlusal contact force levels can be accurately recorded with the T-Scan 10 Novus technology from within contacting and excursing teeth. Then, T-Scan 10 time and force occlusal metrics can treat the occlusion to high precision by performing computer-guided occlusal adjustments. Multiple studies show that T-Scan 10/BioEMG III-guided occlusal adjustments reduce the causative occlusal neurophysiology of TMDs, while both mock and unmeasured occlusal adjustments have been unable to do so.35,82–85

These Key Points authors have ignored the extremely well-supported neuro-occlusal TMD etiology, and Key Points 4 and 6 also ignore the diagnostic and treatment capabilities of the synchronized T-Scan 10/BioEMG III measurement technologies. T-Scan 10/BioEMG III guided Disclusion Time Reduction (DTR) selectively treats the micro-occlusion’s neurophysiology, utilizing high-precision, time-based occlusal adjustments that remove microscopic, but prolonged and excessively forceful interfering contacts.61,62,64,86–103 This minimally invasive computer-based occlusal adjustment technique has repeatedly eliminated TMD symptoms in TMDs treatment studies, performed by many different TMDs treating clinicians on very different patient populations.61,62,64,86–103

Oral appliances and posture

It is not necessary to describe here the many versions of oral appliances that have been designed for specific therapeutic effects in the treatment of TMDs. Even the INfORM authors admit that a generic flat plane appliance can be useful for TMDs treatment. Looking at TMDs patients as having just a jaw and two joints is too limited considering the anatomy is connected to the rest of human body. These 10 Key Points made no mention of obstructive sleep apnea, torticollis, vertigo, tinnitus, nausea, or postural issues as if they are all presumed to be somatic symptoms. Only symptoms that are never physically caused may be distinctly identifiable as somatic symptoms. All symptoms that can be associated with physical causes, must be treated as such until a physical cause can been denied.

The Survey Results from Fifty-two Active TMDs Clinics

Fifty-three successful TMDs treatment providers from 8 countries in Europe, Asia, North America and South America were surveyed to determine to what extent they concurred with the 10 Key Points. The survey was designed to evaluate the 10 Key Points for credibility and applicability within their own TMDs clinics.

The Respondents

Their Responses: Eight respondents indicated less than four years of experience treating TMDs, ten indicated less than eight years of experience, and thirty-five more than eight years of TMDs treatment experience. Six currently treat less than six TMDs patients/year, four currently treat less than twelve TMDs patients/year and forty-three currently treat more than twelve TMDs patients/year. The primary criterion for participation was that these practitioners routinely offer any type of treatment to TMDs patients, rather than referring them out to other practitioners.

Key Point #1 (majority disagreement)

The responses from the 53 providers showed that 94 % disagreed with Key Point #1, indicating a common focus on diagnosing and treating TMDs etiologies (root causes) rather than just learning to “control and manage the symptoms.” Only three of the respondents (6 %) agreed with Key Point #1 limiting their focus strictly to just pain reduction.

Key Point #2 (Majority agreement)

Ninety percent of the respondents agreed with the statement that “TMDs are a group of conditions that may cause signs and symptoms, such as orofacial pain and dysfunction of a musculoskeletal origin.” Only ten percent of the respondents disagreed with that statement.

Key Point #3 (Majority agreement)

Ninety-eight percent (all but one) of the respondents agreed that TMDs etiologies are multifactorial (multiple), while one respondent indicated that the TMDs etiology (singular) is only biopsychosocial.

Key Point #4 (Majority disagreement)

Five respondents (10 %) agreed with Key Point #4, while 48 respondents disagreed with Key Point 4 (90 %), indicating the patient history and clinical examination together are not widely accepted as being sufficient to accurately diagnose most TMDs.

Key Point #5 (Majority disagreement)

Fifty-eight percent of respondents indicated that they cannot fully anticipate what impact TMJ imaging will have on the diagnosis or treatment outcome for TMDs patients prior to obtaining them. In contrast, twenty-two respondents (42 %) indicated that they can usually anticipate the impact of imaging in advance. However, 82 % of those (all but 4) indicated that they would obtain TMJ images anyway to be sure their preconceived structural belief was corroborated. That suggests 92 % of the respondents valued obtaining TMJ images from TMDs patients.

Key Point #6 (Majority disagreement)

All 53 respondents pursue up-to-date knowledge of TMDs diagnosis and treatments, but only 7 agreed with the statement on lack of support for technologies, while 46 disagreed.

Key Point #7 (Majority agreement)

In general agreement with Key Point #7, fifty-two respondents (98 %) pursue reduction of pain, measure functional limitation improvements and avoid exacerbations.

Key Point #8 (Majority disagreement)

Only one respondent (2 %) indicated that cognitive behavioral therapy was useful. Two respondents (4 %) agreed that self-care with medications was an option, while three respondents (6 %) indicated that physiotherapy was also a TMDs treatment option. The rest of the respondents (90 %) indicated that either T-Scan 10 and/or occlusal appliances were their treatment choices.

Key Point #9 (Majority disagreement)

Only two respondents (4 %) agreed with Key Point #9, indicating they never adjust the TMDs patients’ occlusion. In contrast, disagreement resulted from ninety-six percent of the respondents. Fifty-eight percent reported adjusting the occlusion with the T-Scan 10, and thirty-eight percent altered occlusion with various other methods.

Key Point #10 (Mixed response, those in disagreement with higher percentage of success)

Thirty respondents (58 %) agreed with the Key Point #10, while twenty (40 %) were not in agreement. Two respondents (4 %) had completely different ideas. The 31 respondents agreeing with Key Point 10 estimated their TMDs treatments resolved all TMDs symptoms 77.4 % of the time, while the 22 in disagreement estimated their treatments successfully eliminated all TMDs symptoms 86.4 % of the time. See Table 1.

Final considerations

Based upon a comprehensive review of TMDs literature and a survey conducted with 53 leading clinician specialists in Temporomandibular Disorders (TMDs) and Orofacial Pain, it is concluded that the proposed 10 Key Points do not represent a scientifically acceptable standard of care for diagnosing and treating TMDs. These 10 Key Points exhibit systematic scientific bias by neglecting essential orthopedic, occlusal, functional, and etiological factors crucial for an accurate approach to Temporomandibular Disorders. Moreover, they ignore the use of objective tools necessary for a rigorous diagnosis, therapeutic outcome measurement, and treatment stability evaluation.

Critically, these 10 Key Points contain internal contradictions among the authors, which undermine their foundational premises. For instance, some authors dismiss the efficacy of electromyography and other diagnostic technologies in one statement, while simultaneously publishing studies that rely on these tools’ diagnostic value.104–107 These authors have also previously claimed that TMJ clicking and crepitus are common symptoms of internal derangements, yet they claim that asymptomatic subjects also often have apparently non-diagnostic TMJ clicking.108 TMJ clicking due to an internal derangement is either a symptom or not a symptom. It can’t be sometimes a symptom and other times not a symptom. This inconsistency calls into question the reliability and coherence of this entire set of recommendations. Such contradictions reveal a selective interpretation of evidence that compromises scientific integrity and further weakens the credibility of these 10 Key Points.

Overall, these guidelines constitute not only stagnation, but a regression grounded in pseudoscientific assumptions, disregarding well-established physical etiologies and widely used diagnostic technologies such as surface electromyography, jaw tracking, and “computerized occlusal” analysis. These tools are internationally recognized for enhancing diagnostic accuracy and treatment success. Therefore, these 10 Key Points cannot be regarded as “Evidence-Based” or as a “Standard of Care” for the diagnosis and/or treatment of Temporomandibular Disorders. It is evident that a large proportion of dental scientific literature has been overlooked or set aside by these authors. See the following references.

FUNDING

No funding was provided from any source for this project.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts were disclosed by any of the authors.

ADDENDUM

-

Lobbezoo F, Visscher CM, Koutris M, Verhoeff MC, Al Jagshi A, Baad-Hansen L, Beecroft E, Bijelic T, Bracci A, Brinkmann L, Bucci R, Colonna A, Ernberg M, Giannakopoulos N, Gillborg S, Greene CS, Heir G, Kutschke A, Lövgren A, Michelotti A, Nixdorf DR, Nykänen L, Pigg M, Pollis M, Restrepo CC, Rongo R, Rossit M, Saracutu OI, Schierz O, Stanisic N, Val M, Voog-Oras U, Wrangstål L, Bender SD, Häggman-Henrikson B, Durham J, Manfredini D; International Network for Orofacial Pain and Related Disorders Research Methods (INfORM)). [Key points for good clinical practice in the field of temporomandibular disorders]. Ned Tijdschr Tandheelkd. 2025 Jun 10;132(6):318-321. doi: 10.5177/ntvt.2025.06.24131.PMID: 40958643 Review. Dutch. NOT OPEN ACCESS

-

Nitecka-Buchta A, Baron S, Walczyńska-Dragon K, Pihut M, Kostrzewa-Janicka J, Kijak E, Więckiewicz M, Osiewicz M, Gałczyńska-Rusin M, Wieczorek A, Sędkiewicz J, Manfredini D. Temporomandibular disorders: INfORM/IADR key points for good clinical practice based on standard of care: The Polish language version. Dent Med Probl. 2025 Jul-Aug;62(4):565-567. doi: 10.17219/dmp/208377. Polish language version. OPEN ACCESS

-

Manfredini D, Kandasamy S. Temporomandibular disorders: Do we finally have a consensus standard of care for dissemination? Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2025 Oct 9:S0889-5406(25)00383-X. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2025.08.017. OPEN ACCESS

-

Manfredini D, Bender SS, Häggman-Henrikson B, Durham J, Greene CS. Temporomandibular disorders: A new list of key points to summarize the standard of care. Jpn Dent Sci Rev. 2025 Dec;61:1-2. doi: 10.1016/j.jdsr.2024.12.001.

-

Manfredini D, Häggman-Henrikson B, Al Jaghsi A, Baad-Hansen L, Beecroft E, Bijelic T, Bracci A, Brinkmann L, Bucci R, Colonna A, Ernberg M, Giannakopoulos NN, Gillborg S, Greene CS, Heir G, Koutris M, Kutschke A, Lobbezoo F, Lövgren A, Michelotti A, Nixdorf DR, Nykänen L, Oyarzo JF, Pigg M, Pollis M, Restrepo CC, Rongo R, Rossit M, Saracutu OI, Schierz O, Stanisic N, Val M, Verhoeff MC, Visscher CM, Voog-Oras U, Wrangstål L, Bender SD, Durham J;

-

Manfredini D, Bender SS, Häggman-Henrikson B, Durham J, Greene CS. Statement on a new list of key points to summarize the standard of care for temporomandibular disorders. J Prosthodont Res. 2025 Jan;69(2):viii-ix. Open Access

-

Manfredini D, Bender SD, Häggman-Henrikson B, Durham J, Greene CS. TMD management standards updated. Br Dent J. 2025 Mar;238(5):293. doi: 10.1038/s41415-025-8515-8.